|

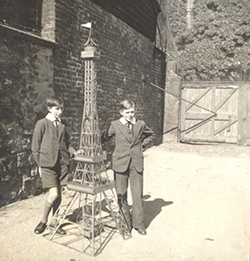

Eric Dare in the school playground. Keith Gibb archive. |

Memories of Exeter Cathedral Choristers' School, 1937-42

Eric Dare (1927–2021), Chorister 1937-42

Version written in 1982, edited by Mike Dobson

[Some photographs are included here, but there are many more of Eric, things he mentions and from the general period, in the two sets of photographs in the Keith Gibb Archive. Editorial comments in the text are shown between square brackets]

I left Exeter Choristers' School after Low Sunday, 1942. Two weeks later, during the German bombing of the city, mercifully in the holidays, the School received a direct hit. An era had come to an end.

|

Eric Dare's original typed manuscript. |

|

Most of the choristers. Eric Dare is back row, centre, in front of the door, wearing mortar board. Keith Gibb archive. |

Some would say that the end was long overdue. Certainly the School of twenty choristers and seven probationers would never have been approved by any outside inspectorate. We were at the mercy of bullies both amongst our fellows and from some adults who could well have been prototypes for the novels of Charles Dickens. In this environment, our lives consisted of fierce contrasts: for instance, the treatment we received from our towering Headmaster, known as "Guv", whom to defy was regarded by us as an act of supreme heroism. He would "lam" us, bare bottomed, lying on his study sofa, not only if we accumulated three "Black Marks", but also if we failed to get 95% in his 100% Latin tests on the four verbs, active and passive. Frequently he drew blood with the back of a long-handled clothes brush. On the other hand, the boy who came top would receive a ten shilling note to spend at Freeth’s High Street confectioners - and that was when Cadbury's bars with their delicious fillings were twopence each!

Each day began with a maid, either "Gussie" or Wheezie", clanging a handbell around the four dormitories to rouse us; then to the large bathroom with its two baths filled with cold water and a plunge that was, needless to say, as quick as we could make it. On some mornings we had thirty minutes prep before breakfast. The unvarying menu by which we could tell the day of the week is with me still - for years I couldn't believe it was Wednesday if I hadn't had for breakfast a cold mackerel soused in vinegar! How I loathed Saturday lunch with stewed rabbit and sticky rice pudding! No question of not eating it: standing over us, with her huge bosom about our ears, was the matron, called "Nurse", having been that to the Headmaster's five children. "Eat it up; eat it up! It's all good meat," she would shriek. "But it's black," I objected. "That's only the blood where it got shot!" Only the roast dinner on Sundays do I remember with pleasure.

It was Nurse who administered Malt, Virol, Cod-liver Oil, and the like provided by one's parents. If one could persuade them to buy the more expensive Malt it was a spoonful of delicious toffee-tasting "goo"; others had an obnoxious oily fish taste, worse even than Wednesday's breakfast. Such health aids were optional; compulsory were the daily gargles of cloudy-coloured liquid - "Izal"? "Jeyes Fluid"? - that quite desensitized one's throat [Eric probably means TCP Liquid Antiseptic, which used to be a common thing to gargle to help sore throats from when it was introduced in 1918. Izal was a shiny, waterproof, medicated toilet paper commonly found in school toilets (and work places) for much of the 20th century; it was abrasive and actually painful to use! Jeyes Fluid is a surface disinfectant cleaning product.]. Sometimes it was a lump of sugar with iodine, for which, though horrid to some, I acquired quite a taste. These and quinine, if one had a temperature, were the only medicines I remember.

|

Rev. Langhorne, "Guv", Headmaster. Keith Gibb archive. |

The standard of education was abysmal - except for Latin and Maths. Geography was taught for an hour in the evening by a lady from Maynards Girls' School we were happy to have lean over us marking our maps! Normally in the evenings we would have Prep - except Saturdays when we sent home our weekly letter and at which time "Guv" would dictate our weekly marks and form position. French was haphazard. For English Literature we were given a potted biography of Milton, though my introduction to Shakespeare was very exciting with "Guv" reading and acting Macbeth and all three witches in appropriate voices. I still remember him in his extra thick, crêpe soles and baggy, blue corduroy suit bouncing round in a circle and heaving his arms up and down with the incantation, "The weird sisters, hand in hand." I don't think we ever progressed beyond Act One. English Grammar consisted of constant warnings of the perils of splitting infinitives and an unvarying list of spellings: I've never had problems with "harass" and “embarrass". We also imbibed bits from Treble & Vallins's "A B C of English Usage", still one of the best books of its sort. History always seemed to be about the Civil War and the Battle of the Boyne. We also had to learn chunks of "Carter's History Notebook", an invaluable handbook I still refer to. ("Idiot! You've ended with a preposition: black mark!" Ah, we learned the important things in life!)

|

|

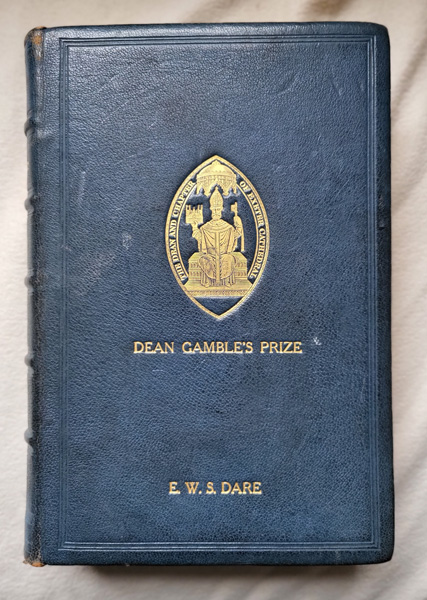

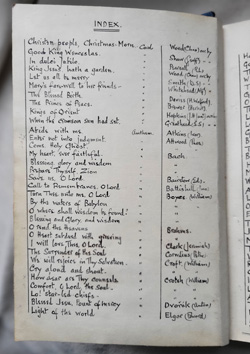

Eric's Dean Gamble's Prize. Now in the Cathedral Library. (click on contents page to see larger version) |

There was no Science and no Art. We imbibed our Religious Instruction from the daily lessons in the Cathedral where each boy had to follow in his Bible. Every year or so was held the exam for Dean Gamble's Prize. In my year it was on the Prayer Book - "Guv" was a 1928 reform fanatic. Apart from winning a handsome prize of some sixty anthems, personally chosen, and bound by Elands in blue morocco, I have always been grateful for the Prayer Book knowledge thus instilled.

The "library" was a couple of shelves of ancient novels with gold-leaf lettering - G.A. Henty, Ballantyne, etc. I remember attempting Dean Farrar's classic since I was always being called "Eric, or Little by Little", but the story was too sad for me to conclude it: we had enough misery in our own lives! Every weekend our own "weekly" would arrive, according to the wishes of the parents. Most boys had comics, Beano, Tiger Tim, Hotspur; but mine, more puritanical, insisted that I had Arthur Mee's "Children's Newspaper". No one would ever swap and I had to be content with literally stealing reads from other boys' lockers.

We were far more inventive, I think, than today's chorister - we hadn't television, radio, electronic gadgets - we had to make our own amusements in the very little free time we were permitted: usually an hour or so after evensong. A great resource was the Cathedral lists printed on stiff card which we choristers distributed weekly around the Cathedral and houses in the Close. From the old lists we made cigarette card machines that dispensed a card for 2d, or it might have been a toffee; or we made extravagant gliders that actually sailed across the common room, launched atop the old wooden lockers; or we made copies of Dover patrol, Monopoly, Buccaneer - or whatever original game a boy had brought back to school. We gambled on some of these games, invariably for cigarette cards.

We had other games in the enclosed yard that was our playground. Apart from football with painted posts, cricket on coconut matting, we had "Snob" a sort of cricket with a soft ball; roller skating when the craze was in; and follow-my-leader that took us perilously across the top of walls and up the outside steps to the singing room with a jump of ten feet to the asphalted surface of the playground: I was not the only one to limp across the Close the next day! We played all varieties of "Tag". A special delight was to invite "Baldie" (Dr Wilcock, the organist) to take a turn at the wicket and tempt him with an easy lob to hoist a cricket ball over the four-storey office buildings of Bedford Circus that looked down on us. On one occasion a chorister tried it in the other direction over the high wire netting and broke the nose of the Archdeacon's wife as she basked in a deck chair.

|

The school playground, with the rear of Bedford Circus visible behind. The boys are making their way to the singing school, for rehearsal. Keith Gibb archive. |

More orthodox sports were soccer at a field beyond Heavitree on Wednesday afternoons, and in the summer, cricket at St James's. This we played also on a Sunday, having trooped out of Evensong before the sermon. Adjacent to the School was the Bishop of Crediton's house on whose lawn we played bowls.

Other ways in which the School routine was enlivened included arranged bare-fisted fights in the junior common room with lookouts to shout "Cave", and on one notable occasion, as juniors, we were invited into the senior room to attend a "trial" of a specially loathed senior boy whose chief "crime" was to be one of "Guv's" favourites, sharing the same first two names. But it was in the dormitories that we were the most inventive. On a hot summer's night we would have competitions to see who could eat his toothpaste, or drink his bowl of water put out on lockers down the centre of the room for morning ablutions. In "Boyd" [named after Archibald Boyd, Dean of Exeter 1867-1883], the largest of the dormitories, we played cricket with a bed for a pitch, hairbrush for stumps and longhandled clothes brush for bat. The "ball" was a stud. (Oh, the agony as a small probationer trying to attach stiff eton collars to elusive back studs!) Needless to say we were caught and the ringleaders "lammed" with the "cricket bat" lying trouserless on the "wicket"!

On the prowl at night was Nurse, whose steps and creaks along the ancient corridor we would strain to hear to warn the evening's entertainer. Chiefly we would narrate the plots of the films we'd seen in the holidays, or invent outrageous originals. Or one would read to the rest with the aid of a torch beneath the blankets - I never did recover my "Stories of King Arthur" that Nurse confiscated.

Apart from Christmas, the only grander entertainment we had was an ancient wireless in the senior common room and a cine-projector for silent films. I can still recall the special smell of the stacks of cans of films in Hinton Lake's lending library that we used for a special treat. Occasionally, seniors would be allowed to use the full-size billiard table that stood behind a barrier in the junior room. The senior room had other larger table games such as ninepins that "Guv" would buy the School for Christmas.

|

Keith Gibb, the 'teacher' who lived in, mentioned by Eric. Keith Gibb archive. |

The day would end with "Compline" in a room specially furnished with chairs, kneelers and matting - that is if "Guv" was not too far gone in his cups. Boys in the senior dormitory, "Quivil" [named after Bishop Quivil (variant spellings including Quivel and Quinel), 1280-1291], might also see him again later in the evening. I remember how it was soon after I moved into this dorm. It was the middle of the war, food was rationed, and in any case we never had enough. It was a novelty, therefore, when the Head and his one assistant, a youth only a few years older than ourselves and the only "teacher" who lived in, arrived in "Quivil" with a tin of baked beans and a spoon saying we could all share in a feast.

Another memory was the occasion two boys ran away. Why they should do so was obvious; how they eventually reached North Devon, I don't know. They escaped one Wednesday evening but were fetched by "Guv" by the middle of the following day, and were then beaten. (The time for execution was always after a weekday lunch) The boys were heroes in our eyes, and although we feigned ignorance of their leaving, most of us knew since they had sold off most of their treasures for small sums of money or food, believing they would never return. If conditions were harsh, perhaps parents could not quibble. Although clothes and "extras" mounted up, the actual fees for our tuition were for choristers, £5 per term, £15 for probationers. There was no charge for board and lodging: we literally "sang for our supper" - professionals at the age of ten!

Boys rarely had cash in hand since the pocket money we received each Wednesday after lunch was meagre: 3d for the youngest, 9d for the oldest. We mostly went to Chidgeys, a dark little sweetshop in North Street to buy aniseed balls or boiled sweets - whatever was the cheapest for the most. Sometimes we would buy little packets of "cachous", tiny, sweet-smelling pellets that could be secreted between pages of one’s Bible in the Cathedral, for use during, the sermons. Hoarding sweets could be dangerous, however. Once, as I sat at breakfast, I felt a sort of shuddering on my shoulder, but thought little of it until it happened during choir practice. I gave a boy 1/2d to stick a pin in a lump in the corner of my jacket. When he did so the whole jacket came alive and I flung it to the floor. My "fizzes", left in my coat overnight had attracted three mice! The more abstemious used their pocket money to build their stamp collections, a favourite hobby. If there was a special craze then we could ask for extra amounts that always had to be justified, such as buying roller skates at 7/6d; or for a similar sum, model aircraft that approximated to a "Spitfire" or "Hurricane" that would actually fly, the propeller turned by elastic.

Our pocket money accounts were generally fairly healthy; indeed there were times when we took home more money than our parents had given us at the start of the term. This was due to the weddings and funerals for which we received half-a-crown a time. Generally we preferred funerals or memorial services since they were shorter and the music less demanding, although I shall never forget my first funeral. The coffin was placed between Can. and Dec. stalls in the nave with four candles at the corners. During the playing of the Dead March from "Saul" I was startled by the sudden noise from the coffin. It turned out to be the candle grease noisily spilling onto the candlestick! At one stage during the war, the organ could not be used and "Baldie" played the piano, and so for funerals we had Chopin's "Marche Funèbre", infinitely more moving.

Another form of income was the annual Red Cross Competition at the Barnfield Hall where we spent a Wednesday being accident victims who were bandaged, hoisted onto stretchers and otherwise tended (more tenderly than ever our own "Nurse" responded - those painful ear inspections!) For this we received five shillings. The best revenue, and most dangerous, came from wealthy patrons of the Cathedral who would slip us a pound or two with a wink and a "Keep it to yourself!" We were unlikely to hand it over to "Guv". Like squirrels, we had our own favourite caches. Since I was learning the organ I had reason to go to the singing room at odd times where there was a small hand-blown instrument. My "safe" was the base of a removable organ pipe.

|

The interior of the singing school, with the organ mentioned by Eric. See page for 1912 |

As an organ pupil whose lessons were on the great Cathedral Willis? organ, I was allowed to practise occasionally on summer evenings there after the Cathedral was closed. Alone in that vast building and aware of my little skill, I never dared to use other than the softest stops. I was therefore startled out of my wits when, as I played, I accidentally touched a piston beneath the manual to produce a sudden blast from a full organ while all the stops shot out at me. I thought of all those venerable corpses aroused from their resting places. It seems incredible that I could be entrusted with the keys and security of the building by Mr. Hart, the Head Verger. What treasures were at risk! But in what schools, other than a Choristers' School, are young boys given responsibility?

There was, of course, the enormous joy of making music on almost every day of the week, the only "plain" services being on Wednesday and Saturday morning. Choral communion replaced Matins on Saints' Days and was an additional service on two Sundays a month. Psalms were in plainsong on Monday mornings; all services unaccompanied on Fridays. Allegri’s "Miserere" was sung at Evensong on Fridays in Lent, the Litany at Matins. These were the regular services. There were the special occasions, too. I loved the pomp and colour of the Assize services attended by judges and civic dignitaries. On St. Peter's Day we processed around the nave and after the service joined in the special tea provided in a marquee in the Close by the Friends of the Cathedral. Nicknamed a "bun-fight", it very nearly was, as we filled our bellies that were usually so empty. I doubt if onlookers then made the sort of remark we used to hear as we filed across the Close from School to Cathedral each Sunday in our eton collars, "bum-freezer “suits and mortar-boards: "Little angels, aren't they!" We used to join the Exeter Choral Society for their performances with what seemed the minimum of practice. My first experience of this was "Elijah" in 1937 with Isobel Baillie as one of the soloists. No treats for us after these performances. On one occasion all we had before being sent to bed was a mug of greasy soup!

Sometimes there was the opportunity for quiet fun; for instance enjoying the relevance of the words we were singing. Who among us did not think of "Guv" as we sang Psalm 78 ("He smote his enemies in the hinder parts and put them to a perpetual shame.")? Or the penetrating altos we had pre-war whom the ironic Wesley makes sing in "Ascribe unto the Lord" ("feet have they and walk not, neither speak they through their throat"). We resisted the temptation, however, except to the amusement of "Baldie" at practice, to imitate the Chancellor, who bleated his vowels like Larry the Lamb, when singing the solo recitative in "Hear my Prayer": "My heart is sorely pa-a-ained within my bre-e-east". We had nicknames for our regulars, such as Timothy and Titus, who later brought along a third and had to be re-christened 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, Titus. It was the days of "ITMA" [It's That Man Again - BBC radio satirical comedy programme that ran from 1939 to 1949] so we had our Claude and Cecil; also an evil-looking gentleman who had to be "Fumph" [all characters in ITMA].

In our vestry were tins of thick grease to ensure that our hair was in place. We mostly made little use of it except when the Bishop attended. Before going to the High Altar to give his final blessing he would bless each chorister with a "laying on of hands". Did he have a hidden rag up his sleeve, I wonder? It was our custom also to put "Pa" and "Ma" in front of surnames and then rearrange the stresses. For instance, Miss Reader, a French and piano teacher, was known as "Marry-a-dor"; "Paka- Neddy", the superb tenor on Decani, Mr. Kennedy.

How and when "getting the red hot poker" was started, I don't know; but it was a tradition that all choristers on being left behind at Evensong prior to being formally installed were branded with it. All choristers swore to the curious probationer that they had thus been initiated.

As choristers we performed other duties such as distributing and collecting music, lists, books. Those who had been confirmed used to serve for early morning communion during the week. Most of us left the School with a portrait of ourselves resplendent in our serving robes of alb and amice.

|

Dr Wilcock, "Baldie", Organist. Keith Gibb archive. |

There was considerable tension, I believe, between the resident clerics and staff of the Cathedral, most of it centred on "Guv" who was also Priest Vicar. His favourite phrase which we loved to imitate, "The man's a fool!", was used especially for the Dean and Succentor, both Cambridge men and thus inferior to "Guv" of Balliol. It was doubtless an antipathy between Dr. Wilcock and "Guv" (though the former freely drank his whisky!) that caused "Baldie" to make me promise not to tell "Guv" about my audition he had arranged in the holidays with HMV [His Master's Voice record company].

Of all the contrasts we experienced, none was greater than Christmas. In the Cathedral we changed from the drabness of Advent to the gaiety of the Festival. If you were a soloist, especially on Decani, you had the excitement and also the responsibility of setting it all in motion at Evensong on Christmas Eve with your "Hodie nobis caelorum rex..."of the Grandisson service, sung unseen, and unaccompanied behind the High Altar, the Cathedral unlit, as I remember it, except for the candles the Dec. and Can. soloists carried down the Quire to the Nave altars, repeating the Good News. Later in the service, a procession with carols sung from the West end. On the following Sunday afternoon, there were carols from the Minstrels’ Gallery. For one Christmas, the B.B.C. recorded “Three Kings" (Cornelius) and "In Dulci Jubilo" (Pearsall). Today when everyone can record everything, this is a commonplace; in 1940 it was quite a novelty. But it was still not possible to make a private recording – I shall never know what I sounded like as I sang the solos in both carols.

The joyful atmosphere in the Cathedral was even more evident in the School, for after Evensong on Christmas Eve we returned to find the parcels our parents and relatives had sent to us in piles around the common room to be opened then - no time on Christmas Day. Before we went to bed we put our dormitory chairs out in the corridor for "Father Christmas" to find, to whom we had written, c/o the Headmaster, some weeks before. In the morning none was disappointed: Monopoly, Meccano, rollerskates ... In the evening we had a full Christmas Dinner with cider to drink, followed by games in the two classrooms opened out to from one big room. "Guv's" family and friends joined in the fun.

And so began two weeks of festivities with a party almost every night. The Chancellor took us to the sumptuous old Dellers, another victim of the bombing; the Dean gave us a feast in the Deanery followed by a visit to the pantomime at the Theatre Royal paid for and accompanied by the Bishop of Exeter. The only "cost" to us was that our presence in the stalls was known to the performers: (how could they miss us in our eton suits and collars?) and so we always had to sing a verse of the community song to the rest of the audience. Before our super tea at the Bishop of Crediton's we had a faintly intellectual competition with pencil and paper, the winner having the first choice of present - but there was something for everybody, all "quality” gifts. There were visits to all three cinemas, the best outing being combined with tea at Canon Hall's house (now the pre-prep part of the Cathedral School and Headmaster's residence) and, following the cinema visit, back to supper and a game of "Murder". In the dark we ran all over the house; newcomers were encouraged to rush upstairs to flee the murderer only to be astonished by the "ghost" that met them at the top. This was the Canon in surplice illuminated from beneath by a torch. That he could get there so quickly from the downstairs room where he had been distributing playing cards gave rise to all sorts of stories about the house's secret passages.

|

Eric to the right of one of the Meccano models he mentions. Unlike his comment, the models were sometimes actually finished. See those shown in volume two of the Gibb Archive. |

It was also fun to be at School during this time minus the seven probationers and with no lessons - the "choristers' hols" as it was known. In the classrooms we played with our Christmas presents or enjoyed the larger table games "Guv" gave to the School. This was the time some of us attempted to make mammoth models with the complete No. 10 Meccano set that "Guv" possessed - the models were never finished!

Recently other old choristers have been sending me their own memories of those pre-war days. Most refer to the extraordinary and brutal conditions we endured - indeed it is surprising, really, that we still wish to meet as Old Choristers except that there is a parallel with reunions of such people as ex-P.O.W.s: we, I suppose are the survivors. But there is a further reason for remembering, and this with gratitude, that the Cathedral atmosphere, its beauty, dignity and pageantry, the religious experience, the musical training and discipline, the need for individual initiative and responsibility balanced against sensitivity to others in the "team", the insistence on high standards ... the qualities are many: these have moulded our lives and have been an influence for good ever since.

November, 1982

Eric W.S. Dare

edited by Mike Dobson, December 2022