SOME UNRELIABLE MEMORIES

Of an Exeter Cathedral Chorister

David Burns, treble 1952 – 1957

Early days

|

David Burns is back row, second from left. |

Unreliable memories? Well – I can’t be absolutely sure that I’ve even got the dates right! I’ve had to work backwards from secure ground: I know I went up to York University in 1964, following a gap year, as we now call it (though in my case it was the direct result of poor ‘A’ Levels, not enlightened choice!); I know I did ‘O’ levels in 1959, a year early (a poor decision by the school); and most significantly, I know I sang in the ‘replica coronation’ which took place in cathedrals across the land in the afternoon of the real event in 1953 – more of which anon. To have done so, I must have been a newly fledged chorister, following my period of probation – which puts my entry to the Choristers’ School at 1952.

One of the problems of one’s parents dying young is that by the time one is ready to ask some questions it is too late. I would, now, love to know why Mum and Dad thought the Choristers’ School was a good choice for me. Was it to do with their perception of me needing to mix with ‘people like us’? Was it the chance of a prep school type education compared with my village primary school? Did they feel that boarding school was character-forming? How significant was the fact that it was, in effect, free – as we sang for our supper?

I certainly don’t think they were driven by the need to ensure that I had a musical training, as I had not shown any great musical talent as far as I’m aware. (At any rate, none has emerged since – unless Mother Nature is leaving things late just to give us all a surprise!) Nevertheless, I went to have some singing lessons (aged 7) with the local church organist/piano teacher and duly went off to Exeter to attend voice trials.

Life just happens to you at that age. I have no memory of being surprised or otherwise at being accepted: it was simply the next thing that happened in the process of growing up … That said, I was probably delighted to get away from two particular harpies at my school who made life difficult for plenty of kids at the village school besides me.

In at the deep end

It must all have come as a shock to the system: there I was, an only child brought up in reasonably comfortable surroundings (though not spoilt) suddenly finding myself at boarding school at the age of 8. My mother claimed later to have wept buckets on leaving me, but I have no memory of ever being homesick – either at first or at any later point. Given that several of the boys were, and that running away was fairly frequent, this still surprises me – not least because it transpired that I had stepped back into a world which in some respects was almost Dickensian.

I no longer remember his name, but a little boy from Tedburn St Mary was forever running off. Whether he ever made it all the way home before being ‘caught’ I know not.

And then there was a boy emerging from a beating; he was screaming hysterically, sobbing his heart out and yet still finding the spirit and energy to yell his defiance – ‘I hate you! I hate you!’ – in a manner which earned our awed admiration as we peeped through the banisters from the floor above.

A New World – The choir school

|

Exeter Cathedral School - The Chantry (photographed in 2019) |

So – what of this new world in which I found myself? The Choir School itself was housed in an imposing red-brick Victorian building just down the hill from the cathedral and more or less opposite the entrance to the Bishop’s Palace. There may have been exceptions, but we normally had to use the ‘tradesmen’s entrance’ rather than the front door. This involved going through a side gate which opened onto steep stairs leading down to a courtyard containing a well and then getting in via the back door. Here were the original servants’ quarters, I suppose: kitchens, scullery, store-rooms, flagstone floors etc.

I also have a vague memory of a day-room/common room for us to relax in – though the school worked on the principle of the devil making work for idle hands so that very little time-off was built into the regime. This basement level also gave access to the playground which was made up of a small garden (staff only, I think), a tarmac’d area and an area of rough ground. The latter two together provided enough space for us to play chain-he and ‘kingy’ which we did obsessively whenever we had free time. For the uninitiated, this is a tag game where the boy who is ‘it’ has to hit a victim with a thrown tennis ball; that boy then joins the ‘it’ and together they (and all who are subsequently hit) form a team to hit other players until some poor blighter is alone, desperately trying to avoid the rest of the school who pass the ball between them, trying to trap and hit him. Needless to say, there was considerable prestige attached to being last man standing.

(I originally wrote ‘person’ and not ‘boy’ in that description of the game; and you might also wonder about the phrase ‘rest of the school’. Both are significant. This was a very male environment: at that time girl choristers were simply never contemplated – as improbable as female clergy(!); and it’s worth saying that there was precious little about our lives which might not have benefitted from some female input.)

The reference to ‘the rest of the school’ is simply a reminder that the school was, of course, tiny: 20 choristers and 6 probationers. As far as I remember, very little time was spent on individual pursuits and most things were undertaken collectively. Opting out didn’t really seem to happen much. This was reinforced to a degree by an institutionalised strict hierarchy which went by the name of ‘seniority order’. Every queue, every privilege, every activity used ‘seniority order’ as its organising principle, so that all aspects of life tended to have a top-down impetus. Each of us knew our place from 1 (Head Chorister) to 26 (newest probationer) and we shuffled up the system via dead men’s shoes. ‘Seniority order’ gave automatic authority (and bullying rights) over any boy numerically below you – and it was constantly in use in one form or another!

To return to the guided tour, the ground floor housed an entrance hall, the Treneers’ (of whom more anon) sitting room, classroom(s?) and dining room. It all gets a bit hazy from here on up because it seems probable that there was a first floor, housing the Treneers’ private quarters. And where, I wonder, did the other full-time staff (Major Tireman and Jim Woodhouse) sleep? James (or Michael?) West, the remaining full-time teacher, had a bed-sitting room on the top floor along with two (or was it three?) dormitories and some pretty basic washing facilities. The whole top floor was based round a long L-shaped corridor.

The Staff

|

The Rev. and Mrs Trener, at one of the annual Christmas parties given by the Mayor of Exeter for the choir, held in the Guildhall. |

The Rev. Howard and Mary Treneer went by the names Patren and Matren (to rhyme with ‘hat’) – though not to their faces, of course! I have always assumed these curious names were a contraction of Pa and Ma Treneer. As well as being on the staff of the cathedral, Patren was Head of the Choristers’ School. I liked him – relatively speaking. Slightly unkempt most of the time and often with food stains down his front, he had an alarming top set of false teeth which slipped chinwards whenever he laughed – which he seemed to do a lot. He called me ‘Coppertop’ – an acknowledgement of my auburn hair (now long gone!) But this affability was offset by a temper which was worth not provoking.

His wife, I loathed. Very overweight with penetrating piggy eyes and a puffy pale complexion, she waddled her way round the building. I imagine she had some role as matron, but I made damn sure that I kept my minor illnesses to myself rather than submit to her tender mercies! She also taught maths to the younger boys – and this may well be the origin of my dislike. Not a natural mathematician(!), I’m sure I must have tested her patience to the limit. Certainly, there were frequent slaps, clips round the ear and bangs on the head from her pudgy bejewelled hands to underline my stupidity, not to mention the free use of the ruler on our hands. Perhaps I should be grateful: I carried with me into an entire career in state education the priceless lesson that hitting children does nothing to help them learn …

Major Tireman, who taught Latin, was also a full-timer. Elderly and craggy-featured with bushy, greying eyebrows he was irascible to say the least. Misdemeanours were often dealt with by ‘six of the best’ – with his walking stick the weapon of choice. Being elderly, his aim was wayward – with the result that backs of legs and smalls of backs stood to get hit as often as backsides. My one abiding memory of the Major (if he had a nickname. I certainly don’t remember it) involved a practical joke. I have now not the least idea whose bright idea this was, nor who set it up, nor why – but if anything was designed to produce a volcanic reaction there was surely nobody better to target! As you may imagine, we had old-fashioned desks and traditional blackboard and easel. The blackboard weighed a ton and was supported on two pegs which could be moved into about six different holes to adjust the height. During break, just before a Latin lesson, the blackboard was rigged so that the two pegs only just engaged with their holes – meaning that the heavy board was poised to drop at the lightest touch!

We waited, breathless with a mix of anticipation and trepidation: it was going to be dramatic, exciting – but I guess we were all pretty scared of the possible outcome. We didn’t have long to wait! The first touch on the board sent it hurtling towards the floor. I always like to think that the next bit was not part of the planning and that we had simply failed to anticipate the way in which the pyramidal shape of the easel would direct the weighty board straight down the Major’s shins. The roar of pain and fury shook us all and probably suppressed the instinctive nervous giggles which would otherwise have broken out. Silence – apart from a furious snorting from the enraged bull standing before us. I have no memory of the consequences. Suffice to say that misdemeanours on that scale, where an individual could not be identified and nobody owned up, tended to lead to the whole school being ‘gated’ for a set period of time.

Punishments

Given the prevalent use of slipper, cane, ruler and walking stick as the school’s preferred means of ensuring our compliance, ‘gating’ might appear to be pretty lenient as the ultimate deterrent. It was, in fact, brilliantly judged by someone. We absolutely hated it. Now I reflect on it, it’s not hard to see why our free time mattered so much. There was little of it, for a start. As well as getting an academic education, we had to fit in daily rehearsals, at least one sung service every day (except Wednesdays), two on several days and three on Sundays. More senior choristers were also expected to serve as ‘altar boys’ at ‘said’ services [editor's note: i.e. no choir] (though I can’t remember how often). It was a heavy workload, one we were expected to carry out professionally in terms of both musical performance and public behaviour. (I remember being told off by The Dean [editor's note: Alexander Ross Wallace, dean 1950–1960, known as Ross Wallace] who had spotted me picking my fingernails during the Lesson at evensong!) So, in a sense, our free time was a real release from the pressures of performance and public scrutiny and expectation; a chance to be children.

If the blackboard trick did, indeed, lead to a ‘gating’, then it’s unlikely that this would have resulted in the boys’ standard response: many of us were complicit, after all. More normally ‘gating’ was a whole-school punishment for the sins of an individual which he refused to confess to. The prevailing code of honour amongst us was that you didn’t shop said individual to a member of staff (assuming you knew him); instead he was condemned to Slipper Alley. This decision must have been made by the prefects, I suppose. They used to slipper younger boys – though I have no idea whether or not this was authorised. Suffice it to say that Slipper Alley involved the whole school lining up along the length of the top floor corridor (which included a right-angle bend) – in seniority order, of course – with legs apart, forming a tunnel. The miscreant then had to crawl the gauntlet through the tunnel. Every boy was entitled to give the poor unfortunate a whack with a slipper, while the prefects could hold him with their knees and hit him as often as they wished. Given that the Alley went directly past the room of one of the Housemasters, it’s hard to imagine that this whole process took place unbeknownst to the staff: and it was, after all, in line with the school’s general punishment ethos, hard though this is to imagine as routine corporal punishment fades into history.

But to return to the staff…

James Woodhouse, a full-time member of staff, was universally liked and admired. A tenor in the cathedral choir, he was good-looking, taught French, football and geography (at least) and belonged to the ‘firm but fair’ school. I certainly have no memory of him hitting anyone. Towards the end of my time as a chorister he married Miss (Vera?) Mapledorham (sp?). I don’t remember her role in the school other than the fact that she taught me the piano – at which I was hopeless! No matter – I would have happily gazed at her indefinitely, even as she tapped my wrists with a ruler as they sagged below the keyboard! I remember blazing blue eyes, red hair and a slim figure. They made a handsome couple, as we sang at their wedding and then attended the Reception at a posh hotel somewhere down towards St David’s station [editor's note: this was most probably the Imperial Hotel, now a Weatherspoon pub].

[editor's note: (with thanls to Philip Hobbs for this information - see editorial comment at the end) James Woodhouse, knowm as Jim, became Headmaster from September 1958 to the end of the Spring Term 1959, as well as being one of the tenor lay vicars. He was replaced as Headmaster by Reginald Pitkin, who was promoted to that office by the Dean, from having been appointed as the school's Bursar by the Dean. James left the school when Pitkin was made Headmaster. It is thought that James married Pamela Mapledoram - information provided by someone who had been at school with her.]

Weekly routine

|

Kenneth Smailes. Information from Richard Salter (treble 1952–57; died 2009): “a Jack-of-all-trades if there ever was one! He was apparently an orphan taken on and helped by the Treneers. He continued to live and work in the Treneer household after their retirement. A fine (if slightly scary) fast bowler when he joined in the summer playground game of Tip-and-bunk (Hit-and-run cricket) during breaks in the Chantry.” |

Little detail of our daily routine remains now, though I do remember the cold bath every morning. We would line up, naked, and under the watchful eye of a member of staff each would leap into the freezing bath, execute a ‘crocodile roll’ and leap out again. Anything less than full immersion resulted in a second dip. The school may have had heating, but I’m pretty certain it didn’t extend to the dorms, which would at least have been philosophically consistent with the open bucket each dorm had for peeing into. This was followed by a brisk walk (more crocodiles!) round the grounds of the Bishop’s Palace and back for breakfast. Somehow Ken (the Treneers’ general factotum) [see right] contrived to burn the porridge most mornings and the very thought of it makes my throat constrict even now. Then over to the Chapter House for choir practice before lessons started.

Mention of breakfast reminds me how foul the food was in the main. The country was only ten years on from the Second World War of course, so the entire nation was probably enduring some pretty grim fare one way and another. From time to time a dish appeared that many of us simply couldn’t stomach – sloppy steamed white fish and tasteless grey stews consisting largely of gristle were my bętes noirs – but we had a solution: the well in the back yard! Surreptitiously a hankie was placed on the lap and, when no member of staff seemed to be looking, the offending plateful was gently tipped onto hankie, four corners tied and resulting bundle carefully slipped into blazer pocket, then down to the well pronto to tip the disgusting mess down into the depths! I don’t recall anyone ever being caught. We were often hungry.

Sunday, however, was a happy exception in that the burnt porridge was replaced by a boiled egg and, bizarrely, an Alker-Seltzer. I cannot imagine what good it was thought the pill would do, but it was always fun watching it fizz in our glass of water. The two prevailing theories at the time show clearly how sceptical we were. One had Patren’s brother as the inventor of Alker-Selza; the other had Matren owning a vast number of shares in the drug company! (Either could, of course, be true!)

Sundays are memorable for other reasons too. For a start there was the discomfort of heavily starched Eton collars and Eton suits (‘bum-freezers’) which we had to wear all day: and it was a hard slog musically with sung Eucharist at 10.00, sung Matins at 11.00 and sung Evensong at 3.00 – and whilst a typical Friday evensong attracted only a smattering of the faithful, sung Sunday services were always showcase events and even had the usual six lay-clerks [editor's note: These are usually known as ‘lay-vicars’ at Exeter. The use of the term ‘lay-clerk’ may simply be an error of David’s.] doubling up in all parts. [editor's note: this refers to the use of 6 'secondaries' or 'Sunday men' to boost the back row on Sundays and major festivals].

Sundays are memorable for other reasons too. For a start there was the discomfort of heavily starched Eton collars and Eton suits (‘bum-freezers’) which we had to wear all day: and it was a hard slog musically with sung Eucharist at 10.00, sung Matins at 11.00 and sung Evensong at 3.00 – and whilst a typical Friday evensong attracted only a smattering of the faithful, sung Sunday services were always showcase events and even had the usual six lay-clerks [editor's note: These are usually known as ‘lay-vicars’ at Exeter. The use of the term ‘lay-clerk’ may simply be an error of David’s.] doubling up in all parts. [editor's note: this refers to the use of 6 'secondaries' or 'Sunday men' to boost the back row on Sundays and major festivals].

Against that were the pleasures of weekly sweets and (in the summer at least) cricket in late afternoon and early evening. Sweets were strictly rationed. Any that we brought with us at the beginning of term were tucked away in a cupboard and released under supervision once per week.

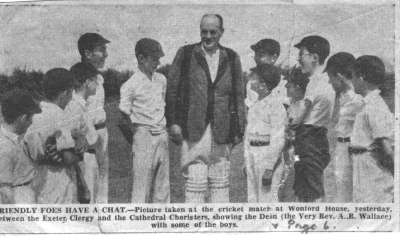

Cricket

|

The boys assembled for cricket. David is on the front row, third from the right. |

Our cricket pitch was out at Wonford, by the imposing mental hospital (which, of course, we always referred to as the loony-bin in those far-off pre-PC days). [editor's note: The cricket area is now occupied by the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital. The mental hospital that David mentions, still exists as the old building called Wonford House, now the mental health section of the hospital. This area had been used for cricket by the choristers for some time, as Eric Dare, chorister in the early 1940s has mentioned this to me, when identifying locations on some old photographs from that period.] Google now tells me that it’s a mile and a half’s walk from cathedral to hospital – which seems quite a distance at the end of a demanding day (not to mention the walk back again). But somehow, we simply took it in our stride (!) and got on with it. As far as I remember, there was no crocodile: we simply made our way there as groups/individuals – which is consistent with the way we were allowed to spend our free time (of which more anon). Our kit and a few lucky boys would join Reggie Moore (organist and choirmaster) in his mighty Humber Super Snipe for the trip. [editor's note: Reginald Moore (1910–1968) was organist at Exeter 1953–1957. He followed Alfred Wilcock and was succeeded by Lionel Dakers. One of his distinguishing features was being 6 foot 4 inches tall. He was also a part-time member of the Music Department at the University of Exeter.] Once there, I guess we usually played Cantoris versus Decani, or maybe Grandisson versus Quivel (the two ‘houses’ into which the school was divided, named after early bishops of Exeter). [edditor's note: The school, being much larger now, is divided into four houses, still named after early bishops: Grandisson, Quivil, Bronescombe and Stapledon.]

From time to time, however, there would be a game in which the choristers took on a team of adults. I have only the haziest memories about who played (the Dean certainly appears in a photo of one such game; (see right) – with one notable exception. This was the Bishop’s elder daughter [see note at the end of this section]. She was large, kindly, outgoing and jolly. We didn’t see a lot of her, but liked her – until she had a cricket ball in her hand. From the perspective of a twelve year-old, the transformation was hair-raising! She would pound in towards the crease and leap into her delivery stride, arms flying as she bowled. If you were facing or still to bat it was not the least bit amusing. If you were one of her earlier victims, it was hysterical ... And then we’d make our way back to school for the best meal of the day: supper. We would line up on the flagstones of the basement corridor to collect a mug of hot milk and – oh bliss! – a half piece of bread and dripping.

From time to time, however, there would be a game in which the choristers took on a team of adults. I have only the haziest memories about who played (the Dean certainly appears in a photo of one such game; (see right) – with one notable exception. This was the Bishop’s elder daughter [see note at the end of this section]. She was large, kindly, outgoing and jolly. We didn’t see a lot of her, but liked her – until she had a cricket ball in her hand. From the perspective of a twelve year-old, the transformation was hair-raising! She would pound in towards the crease and leap into her delivery stride, arms flying as she bowled. If you were facing or still to bat it was not the least bit amusing. If you were one of her earlier victims, it was hysterical ... And then we’d make our way back to school for the best meal of the day: supper. We would line up on the flagstones of the basement corridor to collect a mug of hot milk and – oh bliss! – a half piece of bread and dripping.

[editor's notes - Bishops' elder daugher:

Bishop Robert Mortimer (1902–1976), bishop of Exeter 1949–1973. He and his wife, Mary, had four children: Mark, Edward, Sophia and Katharine (Kate).

- Mark was the Classics master at Shrewsbury School (obituary 2009, written by Edward, The Guardian - https://www.theguardian.com/books/2009/jun/15/obituary-mark-mortimer-classics)

- Edward is also very distinguished, being until 2007 the Director of Communications in the Executive Office of the United Nations Secretary-General.

- Sophia was the older of the two daughters. There is a reference to Sophia in connection with Bangor University, as a member of the student English drama and debating societies (Ann Clwyd (2017) Rebel with a Cause, chapter 3). She married and became Sophia Schutts. She is mentioned in connection with her father’s acquaintance with Agatha Christie, in Andrew Norman Agatha Christie: The Disappearing Novelist (2017), chapter 21. Sophia died in 2016 (source: newsletter of the South Cotswold Ramblers (http://www.southcotswoldramblers.org.uk/messagesarchive.htm and Mike Garner, Webmaster, South Cotswold Ramblers, email received 19th February 2021).

- Kate was a distinguished economist – obituary 2008, The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/business/2008/jul/24/economics.globaleconomy - which also provides the names of her siblings).]

Freedom of movement

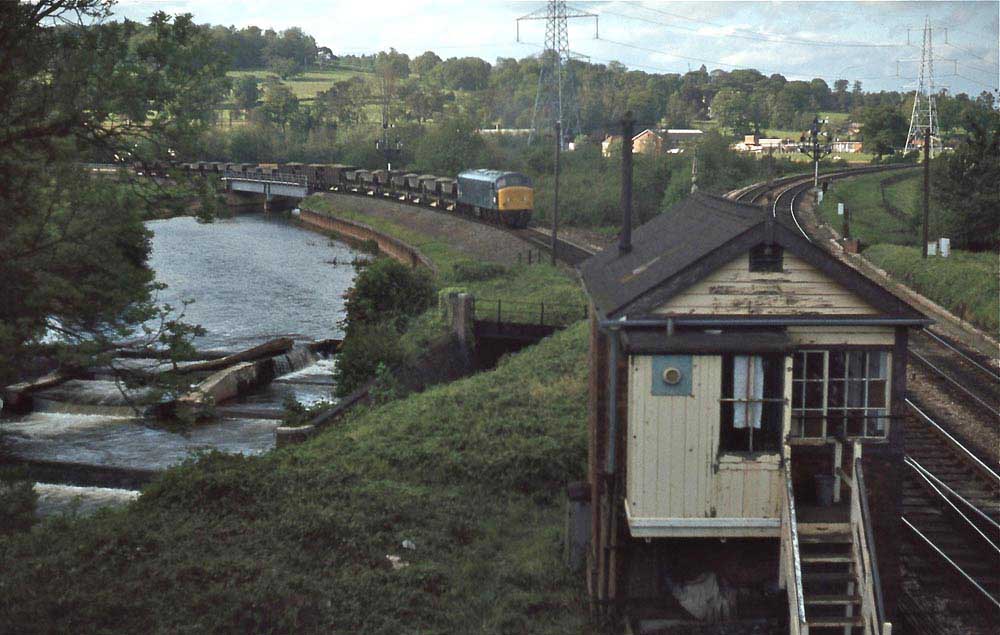

|

The view north from Cowley Bridge, with the Barnstaple line crossing the River Exe on the left, and the main London/Bristol lines on the right. [source: https://www.derbysulzers.com/class45wr.html] |

The school’s attitude to our movement around the city was interesting and we were allowed the kind of freedom which almost certainly wouldn’t be allowed today. As far as I remember, nowhere was out of bounds and we ranged far and wide. There were two prime trainspotting sites, for instance. The farthest away – and it was a fair old step – was at Cowley Bridge which, apart from being on the main West Country line, offered the additional fun of having an Exe salmon-leap to keep us amused when train traffic was slow. Nearer to school, and in some ways more exciting, was Exeter St Thomas station. Here we could get onto the platform and get really close to the oncoming steam express trains as they roared through on their way to Exeter St David’s. I have never outgrown the visceral thrill of seeing and feeling the thunderous passage of a mighty steam engine.

These and other excursions were undertaken in pairs or small groups; but from time to time a great mob of us would head for Rougemont Gardens. How this was set up and managed, how controlled etc., I couldn’t begin to explain – but inspired no doubt by the imposing red sandstone Rougemont Castle, we played some wild and elaborate chase/hide-and-seek game with two teams ranging all over the paths and overgrown shrubberies of the city’s central park area. How often we had this sort of time-off, I really can’t remember – but it was a wonderful chance to let off steam before returning to the standard role of angelic chorister...

Behaviour in the choir

And though ‘angelic’ was, indeed, our default public demeanour, things occasionally went off-script. I remember, for instance, matins one Whit Sunday. This was always (I think) set aside for the annual blessing of the choristers by the Bishop and tended to attract a large congregation (for reasons I don’t really understand!) We knelt in the knave choir stalls and the bish passed along the row, placing hands on each of us in turn and saying: ‘Bless you my child’. About five or so boys before me, the reverend silence of the hushed cathedral was shattered by one of the lay-clerks dropping his copy of ‘Hymns Ancient and Modern’. The version containing harmony is a pretty substantial tome and the choir stalls a near-perfect soundbox – resulting in a thunderous bang which then reverberated round the cathedral. A nudge from my left and a whispered ‘silly bugger’ was all it took to reduce Stephen Davies and me to completely uncontrollable giggles. The Episcopal voice was getting closer – but we were beyond help and the bish found himself blessing a snuffling and shaking ‘Coppertop’!

Once in the vestry, we calmed down – only for our giggling to turn to panic as I was summoned to the Lady Chapel by one of the virgers. For a small boy with a guilty conscience the walk from transept to East End seemed to last for ever. I was certain that the wrath of God would strike me down before ever I arrived, but in due course stood before Bishop Mortimer awaiting my fate. He duly made it clear that he was disappointed by my behaviour but then proceeded to tell a story against himself, involving him and Oxford friends laughing in chapel [editor's note: Robert Mortimer was undergraduate at Keble College] at a deaf old woman who regularly finished saying psalms and responses loudly long after everyone else had finished. It was a humane way of dealing with some innocent naughtiness on my part. Stephen got away with it as far as I remember. Perhaps he had managed to stop giggling before it was too late? (Conspiracy- theorists would relate his ‘escape’ to the fact that his dad was Chaplain on board the mighty HMS Vanguard! We remained friends. His Dad fixed it for a naval rating to take us sailing in Plymouth Sound and I later went out with his sister for a couple of years ...)

Decidedly naughtier was the occasion when, having been altar-boy at 8.00 a.m. said communion, I was putting away vestments and altar vessels in some side vestry. The tasks involved returning wine and wafers to their storage and it occurred to me that I really ought to find out what the wine was like ... Of course, I was caught mid-swig by the Head Virger. He gave me a real telling-off, but left it at that, I’m glad to say: another visit to Dean or Bishop would have been a bit much.

Altar boys

Being altar-boy wasn’t a huge amount of fun. I don’t now remember how ‘senior’ one had to be to be trained up for the role, but I must have been 12 when it fell to my lot to cover the said communion on Christmas Day. Instead of being in one of the side-chapels, the service was celebrated at the high altar – with all the cathedral’s best vessel’s and plate on show and the clergy in their most elaborate vestments. The cathedral was packed with people prepared to forego the celebratory music of the later services in favour of getting their devotions over early before getting home to their families. Also generous people, some making their one annual church visit (just to reassure their Lord that they hadn’t forgotten him).

The end result was the need for extra sidesmen to gather the many well-filled collecting pouches before lining up and rolling in-step down the centre-aisle towards the altar-rail. Awaiting them there, a small boy carrying a vast gilded plate, already uncomfortably heavy. Pair by pair the sidesmen deposit their offerings on the plate. Four, six ... surely there can’t be any more? But still they come ... I haven’t the gumption or nerve to stop them while I go to unload somewhere before returning for a second load. The inevitable happens. I can no longer be sure whether or not the plate went too, but the collection offerings certainly cascaded onto the steps of the high altar – some remaining intact but several spilling their contents ... I’m glad to report that the acute embarrassment of the moment has erased all further detail from my memory!

Music

But what about the music, I hear you cry(!)? Yes, of course, it was our raison d’etre and was very time consuming; yet inevitably relatively little stands out after all these years. What do I remember, though? Daily practice in the Chapter House with a more senior chorister instilling the tempo via an elbow or a hack to the ankle; the huge pressure to get new repertoire under our collective belt or less familiar pieces revised – which meant there simply wasn’t time to dwell on music theory; Reggie Moore’s volcanic temper leading to a chair being chucked halfway down the Chapter House on one occasion, and his fist going through the ornate tracery of wood by the side of the music stand on the grand piano on another.

|

Reginal Mooore can be seen at the far end of the robed adults, his height making him very distinctive. |

It‘s worth saying here that we loved Reggie, temper and all. Sadly, the men and the clergy couldn’t tolerate his tantrums and his tendency to hang out of the organ-loft sniffing his disapproval all too audibly – at, say, a mistake by the choir or some pitch-loss. He left – sacked, I suppose – about a year before my voice broke and I, too, was off to pastures new; my first solo (in a Stanford Nunc Dimittis, I think) which resulted in the following as I was collecting our music from the choir stalls:

Reggie: Was that your first solo, Burns?

Me: Yes, sir!

Reggie: Well – it’s your last!

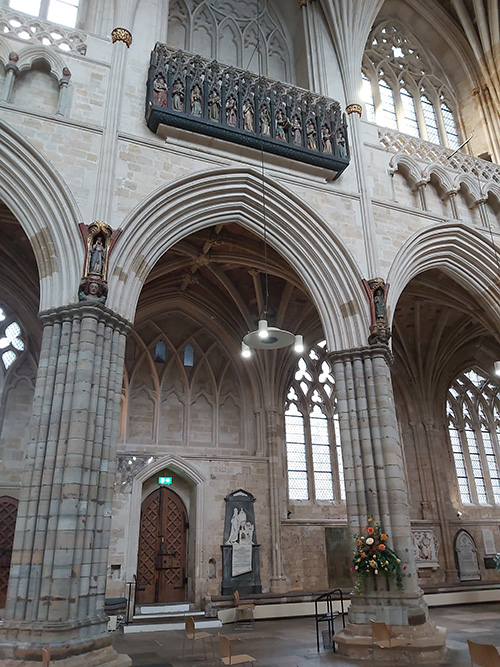

The excitement of the annual Christmas Eve Grandisson service (usually preceded by tea with my Dad at the posh hotel in the Close – The Clarence, recently [editor's note: October 28th, 2016] gutted by fire, sadly) where we processed round the cathedral singing carols at various fixed points; the fun of climbing up hidden staircases to emerge in the Minstrels’ Gallery [see editor's note below] – though who knows why we sang there, or what; the sheer joy of some of the celebratory music at the main Christian festivals; the BBC Radio 3 choral evensong recordings (for which we actually got paid – half-a-crown [editor's note: Two shillings and sixpence, pre-February 1971 currency. Equivalent to 12.5 pence.] per child, rising to five shillings [editor's note: Equivalent to 25 pence] for corner-boys and more for the Head Chorister!); the slightly spooky atmosphere of Friday evensong in Lent: the choir in black, the cathedral only half-lit and virtually empty, the coke smoke from the great stoves hanging in the air and Allegri’s haunting Miserere echoing around us; the ‘imitation coronation’ we sang in the afternoon following the real thing (as was done in every cathedral, I think) [editor's note: The Coronation of Queen Elizabeth was 2nd June 1953.]; the pleasure of knowing that certain favourite anthems were coming up again;

|

A stop by the choir at the Jamaica Inn, 1954, on the way to sing at Truro. Photograph: Philp Hickman (see editorial note at the end) |

the dreadful tedium of singing Byrd masses out of sight in the aisle between high altar and Lady Chapel during Lent; the all-too infrequent special occasions such as the shared services with Truro cathedral (despite the interminable coach journey and inedible Cornish pasties) [see editor's note below]; the sheer terror of page-turning for visiting organists who had come to perform in the weekly winter recital (I should elaborate: at some point we were deemed competent enough to follow an organ score and turn for a visiting organist. Apart from the anxiety of managing to follow often complex and unfamiliar music, the score itself was on a stand across four manuals so that even reaching it to turn was tricky for a small boy. And then one had to be sure that the nod to turn was, indeed, a nod and not just an artistic body movement as the music took over the organist. Some were understanding and gave clear indications, others a nightmare ... All in all, it was pretty nerve-wracking!).

[editor's notes:

The Minstrels' Gallery, high up on the north side of the Nave. [photo: editor, May 2021]

Minstrels' Gallery

Reference to singing from the Minstrels’ Gallery during the Grandisson service is probably a slightly mis-placed memory of David's, as it is during the Christmas Day Evensong that carols are sung from here, and have been for many years (The Illustrated London News, December 25th 1852, has an engraving showing this happening). Philip Hickman, a contemporary of David's [see editorial note at the end] comments: "We did indeed sing from the Minstrels’ Gallery at Evensong, Christmas Day and again on the First Sunday after Christmas – by which time the choristers of today are home for their Christmas holiday. Our Christmas holiday began on the evening of 6th January."

Grandisson Service

(With thanls to Philip Hobbs for this information - see editorial note at the end) The Grandisson Office was first used in its present setting in 1928, with the Hodie Nobis ... responses written by the newly appointed organist, Thomas Armstrong. Then, until 1971, the office formed part of the evensong for Christmas Eve, being sung between the end of the first lesson and the Magnificat. We know that when the Christmas Eve services were changed in 1971 under Lionel Dakers, there was a said Evensong at 4.00 and the newly constructed Grandisson Service at 5.30 (became 6.00 at some point), which had become a festival of lessons and carols, preceded by the Grandisson Office, as we know it today.

Truro

At some point after this, the visits to Truro stopped. When they recommenced, in the late 1980s or early 1990s, when David Briggs was organist at Truro, it was thought at the time to be something new. This memoir of David’s clearly indicates they had happened before. They now occur every few years, with Truro and Exeter visiting each other for a combined evensong.]

Choir Robes

As far as I remember, red was the default cassock colour. There was a black set for Lent and funerals (though I only remember one. Can't remember whose, but do remember the impressively large tallow candles surrounding the coffin. Hard to believe, but it may have been the only funeral we sang at during my time.)

[editor's notes:

Rather than red, the cassocks were actually scarlet. This colour was worn until 2017, when it was replaced by blood red. This change was the consequence of the issue which occurred in the 1980s, of whether Exeter and a number of other cathedrals were royal foundations and entitled to wear scarlet.

Another former chorister has a letter he wrote home which says that black cassocks were worn for when King George VI died (February 1952), presumably in this case, ‘mourning attire’. (information from Ben Liberatore, PhD student, New York, January 2021)]

Christmas

People would often comment pityingly about the dreadful sacrifice the choristers had to make at Christmas – away from home, working their socks off when most children were having a high old time etc. As an only child, my Christmases were probably much more fun amongst my pals – and I still got to enjoy a belated family Christmas as well! I’m sure the school made an effort on our behalf, though I have no memory of what was put on for us once our duties were over.

By contrast, I remember well the annual Christmas parties put on for us by both the Dean and the Bishop. At a time when sweets and party food were a real rarity, both clergy indulged us splendidly – followed by games in the Bishop’s Palace and The Deanery [editor's note: Now the Old Deanery, and the diocesan offices, opposite the West front of the cathedral.]. I still remember being with Kate, the Bish’s younger daughter as we played sardines squashed into a large cupboard on some landing or other. And of course there was always the fun of enjoying everyone else’s new toys as well as one’s own. One way and another the time until Epiphany, when we were finally released, seemed to pass relatively quickly.

There was, of course, no school once Christmas was under way and the prevailing weather and light virtually ruled out the ‘whole school’ activities I’ve referred to above. I have only the haziest memory of how we actually passed the time – with the exception of marble runs. This was a wonderfully creative and wholly absorbing way of passing the time – one which modern school furniture has rendered impossible because it was dependent on a ‘traditional’ desk – a large lidded ‘box’ with ink-well hole at top right corner and marble-sized dust-hole at either left or right of the desk ‘floor’. The basic plan was to create within this cubic space a series of finely angled passages, one above another which would deliver a free-running marble from top hole to bottom in the slowest possible time. As lessons were suspended, intricate constructions could remain undisturbed by the need to extract Kennedy’s Eating Primer (remember it?) [editor's note: explanation of what this comes later] or an atlas – for it was exercise and text books, rulers and any other firm, flat surface we could get our hands on which formed the bases of these elaborate 3-D mazes. It all got very competitive and I’m sure sabotage was not unknown! (Perhaps I should explain that Mr Kennedy wrote a Latin Primer – the cover of which was defaced by the conversion of the ‘L’ into an ‘E’ and the addition of a final ‘g’. I suspect this was universal practice wherever Latin was part of the curriculum!).

Lett’s Schoolboys’ Pocket Book was another source of endless, slightly studious, fun. This slim volume was crammed with facts: capital cities, the ten longest rivers in the world or in the UK, highest mountains, fastest animals etc, etc. In the days before the internet such knowledge probably had more ‘value’ than it does now, and we learned it all up and tested each other as though our lives depended on it! Some collected stamps, some read, some played card or board games and some even practised the piano!

Sundays after choir

Sunday evenings in summer were devoted to cricket, but in the winter the older boys would gather in the sort of common room and listen to the radio. ‘Journey...into...Space’ [editor's note: Journey into Space, BBC Light Programme. Radio broadcast 1953–1958.] or The Goon Show [editor's note: The Goon Show, BBC Home Service. Radio broadcast 1951–1960.] were two favourites. I can’t imagine we made much sense of the latter – indeed, I have just had to check that it really was on air as early as the mid-fifties and not part of an adolescent memory (and am reassured by Google that it started in 1951, would you believe!) Journey into Space was decidedly scary – and we would wind the tension up by listening in the dark (apart from the glow of the valves). That same common room housed a record-player. This may well have been provided by one Peter Iles, because I’m pretty certain the records were. Certainly, they wouldn’t have had official approval – and we may even have been listening illicitly with somebody posted to keep cave. Sadly, all I remember now is some Elvis Presley and Lonnie Donnegan. Rock Island Line was a great favourite with all of us [editor's note: Rock Island Line, released as a single by Lonnie Donegan in 1955.].

Occasionally, Mr. Keene(?) would arrive in his van with an apparent torpedo tube on the roof. Great excitement; for this was, in fact, a container for the screen of his mobile cinema. Laurel and Hardy, Buster Keaton, cartoons and ‘improving’ films all brightened some of our Sunday evenings – though I don’t remember the frequency. The only down side was that, having achieved a certain level of seniority, one was expected to conclude the evening with a vote of thanks to the said Mr. Keene – and there seemed to be an expectation that the ‘spokesboy’ would incorporate some kind of critique of the film as well as thanks! In effect, this meant only paying half-attention to the usually climactic final 10 minutes as one tried to think of something clever and apt to say! (Or wondering how one was going to disguise the fact that the film had reduced one to tears – which I remember happening with The Miracle of Fatima) [editor's note: An American film released in 1952, The Miracle of Our Lady of Fatima, about three children from a small village claiming to have seen a vision of the Virgin Mary.].

Lights Out

Another film I remember enjoying hugely was the 1930s version of The Thirty-Nine Steps – not least because we had had it read to us as a bedtime story [editor's note: A British film, released in 1935, The 39 Steps, directed by Alfred Hitchcock.]. Not everything went smoothly at the school but reading aloud to each dorm at night was something they got spot on. This was before the great heyday of writing for children which really started in the seventies, so we tended to have a diet of Conan Doyle, Dickens, Dorothy Sayers, PG Wodehouse, John Buchan and the like. Put alongside the eloquence of the psalms and the wonderful linguistic treasures of the King James bible, this was an immersion in language which must have stood us in good stead (apart from the feeling of cosy engagement as the stories unfolded. Is there anything that can beat the bedtime story?)

Once lights were out, life in the dorms sometimes veered back towards the Goldingesque [editor's note: A reference to William Golding’s 1954 novel, Lord of the Flies.]. The real problem was that very young boys were given too much power; and the situation wasn’t helped by the concept of ‘seniority order’ which seemed to entrench the notion of everyone having someone to bully or at least chivvy – unless, of course, you were the youngest probationer. I really do not know what the staff knew or approved of, but this kind of thing was not uncommon::

A darkened dormitory, supervised by a 12 year-old prefect. 10 children in bunk-beds. Silence as required.

Prefect: Burns? Are you awake?

Burns: Yes, Smith.

Prefect: What! Did I hear you talking, Burns?

Burns: Well ... I was just -

Prefect: What? Again? Come out here ...

There would often follow one/three/six whacks from a slipper on the backside – though some favoured the back of a hairbrush ...

Not all the prefects were like this, of course, and I cannot now remember who and how often; nor can I be absolutely certain that I was above using the slipper when I became a prefect – though I’m pretty certain that my sense of justice was fairly well-developed and I’ve never been interested in playing the bully either as a youngster or as a teacher.

Oddly, talking after lights-out became something of a speciality for me. I’ve not the least idea of how or why it started, but I found myself increasingly called upon to tell the dorm stories. At around eleven or twelve I was an avid reader of just about anything I could get my hands on. I spent my pocket money on second-hand copies of anything by the sexist xenophobe G.A. Henty and his Boys Own adventure stories but would equally happily lose myself in the strip-cartoon love stories of Mirabelle (I think!) [editor's note: Mirabelle was a British cartoon comic, published 1956–1977.]. Chuck in a bit of Ryder Haggard, Charles Dickens, Alexander Dumas, Conan Doyle and Arthur Ransome and a strange derivative serial story would emerge – though the nascent hormones beginning to scent the dorm air made sure that there was always some innocent love-interest to spice things up a bit!

Games and activities

What memories remain have no linking theme. Random and quite unconnected, they take me from the top corridor (of ‘slipper alley’ fame) to the roof of the cathedral; from washing up on Sundays to the riverside when we had time off. The sense of being one large family was re-enforced by our chores: and helping Ken [Smailes - see earlier note] with the stunningly greasy washing up on Sundays was only alleviated by the prospect of sweets. (I still remember being reprimanded for my ungrammatical ‘Sir. Is it sweets?’ in Pavlovian response to a bell round about teatime one Sunday!). And then there was the time a gastric bug hit the school. By chance, I was spared; but the school was awash with vomit and I remember being dispatched to do some mopping up on the top corridor.

A favourite activity when there wasn’t time to go to Rougemont park for a game of cops and robbers (or whatever the elaborate game was) was for a group of us to make our way down past the many remaining bombsites to the quay side. This was a fairly dubious area at the time [see editor's note at the end of this section]. There was always something to see and it felt edgy – though I’m sure our imaginations greatly exaggerated the nefarious nature of the dealings done in the ancient cave storage vaults dug into the cliff face. A recent nostalgia-trip to Exeter revealed the quayside as a buzzing tourist venue, the storage caves converted into chi-chi shops – selling scented candles amongst other things. Our purpose in going down there, however, was quite different. Amongst the dilapidated warehouses and rotting sheds there was one business still functioning all-too actively: a tannery. The smell was disgusting beyond belief and we would challenge each other to stand in the open doorway next to the huge tanks full of hideousness for as long as possible before fleeing!

[editor's note - West Quarter:

The West Quarter of Exeter, in the area to the west of North and South Street (at the western end of the High Street) down to the river Exe, had been a very deprived area and ‘to be avoided’ before the period of these memoirs. Slum clearance in the first half of the twentieth century started to help improve the area.]

Virgers

|

One of the heating stoves mentioned by David, shown here in the north quire aisle. It is a Gurney Stove. They were widely used in cathedrals across the country from the second half of the 19th century. (see: Hereford and Tewkesbury Abbey where a stove being filled in the way David describes is shown, http://www.hevac-heritage.org/victorian_engineers/gurney/gurney.htm for the history of Gurney and his stoves, and Garton & King Ltd, Exeter Foundry who worked on the stoves at Exeter) I was told an amusing story by Ron Melhuish, head virger in the 1960s and 1970s, that he once noticed the smell of sausages cooking in the cathedral. He discovered a tramp was using a Gurney stove to cook on! [editor] |

Although I’d got a good telling-off for my wine experiment, the virgers were generally regarded as ‘being on our side’. Apart from their formal duties such as conducting the senior clergy to and fro, they were often to be found lurking in a side vestry, or somesuch, cleaning silver, and their ‘neutral’ status meant we could talk to them freely in a way which simply wasn’t possible with clergy or staff. Amongst their duties was the stoking of the great coke-fired ovens which vainly tried to keep the building warm in winter. To this end, they could be seen trundling a four-wheeled coke-filled cart on a circuit round the cathedral. Another task which I always enjoyed watching was their skill at putting out umpteen candles on the two huge chandeliers in the nave (which were lit on high days and holy days) using a snuffer on a very long pole. I never once saw them knock a candle out of its holder – and I love the smell of extinguished candle to this day! It only just occurs to me now to wonder how they ever got lit ...

From time to time one or other of the virgers would take groups of us on exploratory trips along the secret walkways, staircases and passages concealed in the fabric of the mighty building. To this day, I have a vivid memory of being in the roof-space of the nave and being struck by the logic of what a vaulted ceiling must be like when looked at upside down, as it were: we walked along the spine in single file, looking anxiously down (in my case, at least) into symmetrical pairs of ‘pits’ either side. What extraordinary feats of engineering, craftsmanship and imagination ... [editor's note: In this period, the roof-space was a single open space between the east and west ends of the buildings, so one could look from end to end, creating a rather strange feeling, with the series of vaulting dark ‘pits’ running off into the distance on both side of the central walkway, that David refers to. In the late twentieth century, a series of fire-break walls was very sensibly constructed along this space, so it is no longer possible to see such a view.]

Life after Exeter

These blurred memories slowly fade into a general indistinct wash, but Exeter left a legacy for which I am truly grateful. Making music has remained a huge part of my life: I continued to sing at secondary school, a bit less at university and then very little for fifteen years or so as the demands of a career in education took precedence. That said, it was through music at university that I met Sarah, my wife. I was singing in the chamber choir (probably the only choir, given York’s tiny numbers at the time!) There, across a crowded room(!) was a cellist – long dyed-blonde hair ... Eye-catching to say the least – and I was well and truly caught. Her father, a good musician, ran the village choir back at home – as had his father-in-law before him. I’m sure I was a disappointment as a son-in-law in many respects – but the first and greatest of these was that I was not a tenor!

Then, at about forty, I took up the bassoon. As my competence increased, I found myself more and more involved in orchestras and chamber groups – but with less and less time for singing, of course. I also took the decision to give priority to music-making over the potentially overwhelming demands of the job so that school governor meetings, requests to talk to PTAs and other similar evening work would have to fit round my regular Monday and Thursday evening music activities. I never excused my non-availability with fictitious ‘previous engagements’ in the hope that others, too, might look at their work/life balance and give a little attention to ‘self’ in what tends to be a largely selfless profession. I am not aware that this attracted any disapproval from the schools I worked with, nor colleagues, nor bosses – quite the reverse, in fact.

With retirement came the opportunity to sing more; and the final impetus came from having to give up the bassoon as I entered my seventies. Alarmed at the prospect of rotting in front of the telly or taking to the streets and bothering elderly women, I decided to sing more (if anyone would still have me). And that is what I do – from full-on (very good) Choral Society to a group of seven friends sitting round our kitchen table; from Bach Mass in B minor to a Bowie tribute written by my eldest for ‘his’ large and surprisingly competent open-access choir; from auditioned chamber choir of twenty-five to Man Chorus (with its two or three droners). Given all this, why the hell isn’t my sight-reading perfect?! Anyway – warts and all – thanks Exeter.

(All mistaken memories are entirely innocent – no malice intended. Apologies for any such errors.)

February 2021

Edited by Mike Dobson, Cathedral Choir

I received the original version, completely unexpectedly, by email from David on 10th February 2021. David had come across me through the ECOCA website. My editing of the original version, to present what is here, includes adding sub-headings and some anonymising. Editorial notes are mine or appropriately attributed. Where the text has ‘…’ these are in the original and do not indicate editorial deletions or changes.

With thanks to Philip Hickman, a contemporary of David's, for very informatiave comments on the memoirs and providing some supplementary details.

Thanks also to Philip Hobbs (former tenor lay vicar) who is researching the history of the choir, for his very useful comments and providing some additional information.