Denis Le Plastrier Vercoe

Chorister from c. 1925 to at least 1928

(edited by Mike Dobson, alto 1976-2023)

Denis was born in Plymouth in 1915. He died in 1995. He was known as Peter, a nickname given him by his elder brother after the character Peter of 'Peter & Pauline' who appeared each week in the periodical called the 'Rainbow'.

A full biography, with autobiographical inclusions, is available online. The excerpt below is a wonderfully long and detailed reflection on his early life as an Exeter Cathedral chorister. My editorial comments are shown in italics between [].

"... that period nearly 60 years ago when I first went away from home to become a chorister at Exeter is still very often and vivid in my mind and these are the times and people I want to tell you about.

As a small boy in Plymouth in the mid twenties I had a playmate John Bingham who lived near us and either I heard from him or my mother heard from his mother that he was going to Exeter Cathedral School [known as the Choristers' School at this time] for tests to see if he could be admitted as a Chorister. It was decided that I should also go and accordingly I was taken to Exeter, whether with John Bingham or on my own I can't remember, and was examined in the choir practice school by Dr Ernest Bullock the Cathedral organist. I must have been made to sing to see if I could sing in tune and had a voice of sorts, and also given something to read to test my reading ability - I remember I was given something which included Johan Sebastian Bach which I pronounced to rhyme with 'clash'. However this apparently didn't bar me from acceptance as both John Bingham and I were admitted as probationers at the Choir School. I can't remember the exact year but I think it must have been around 1925 when I was ten years old.

In those days the school was very small and consisted of only the 20 choristers and 5 or 6 probationers who moved into the choir as older choristers left to go on to other schools when their voices broke. [there were also non-chorister pupils at this time, so the memory of there being only the 20 choristers in the school is probably a distortion]

There followed a hectic period of kitting out for the new life away from home - grey suits with double seated trousers were purchased at Pinder & Tuckwells school suppliers, mortar boards - eton collars -caps with the yellow crossed keys of St. Peter and blazers with the pocket decorated with the same insignia [Pinder & Tuckwell was a very long-established 'traditional' gents outfitters. It had a shop in the High Street - opposite the current Marks and Spencers - into the late twentieth century, when it moved to the upper part of Fore Street, where it only lasted a few years before ceasing trading]. Slowly the brown school trunk filled with all the necessary clothes until the penultimate day came when the railway truck called at our house and picked it up; I hoped I would find it at the school when I arrived. The day of departure was always a sad day for me - I was very bad at going back and only on the first occasion was I seen off on the 4.10 p.m. from North Road. Ever afterwards I would go to the station by taxi on my own having said goodbye to mother at home. At the station I would meet John Bingham, and also Bill Williams, another Chorister from Plymouth and we would travel together to Exeter arriving at St. Davids at about 5.40. In retrospect it is always the winter arrivals that I remember. It was dark when we reached Exeter and we caught the lighted bus outside the station and rode up the hill and along Queen St. to the High St. where we alighted. We crossed the main street to the Close. Gas lamps gave a faint yellow light on the pavements under the trees. Richard Hooker sat on his plinth to our right, and behind him loomed the great dark bulk of the Cathedral. Past Canon McLarens and the Rev. Llewelwyns houses and turned between Reggie's House and the Bishop of Crediton's old house into a dark alleyway [the alleyway still exists, between numbers 9 and 10 Cathedral Close, behind a doorway at the cathedral end], lighted by one gas holder; at the head of this lane a door that filled the lane with a small inner door let into it admitting us to the Choir School yard itself.

On our right on entering, stood the school. Lights shone from all the windows. The basement was the home of the kitchen and kitchen staff and our dining room. The first floor was the classrooms and common rooms where we lived out our life in and out of school time. On the second floor were the two dormitories, named after early Bishops of Exeter, Boyd and Grandison. [Boyd was not in fact an early bishop, but Dean of the cathedral, 1867-1883]

The corridor on the first floor led through into the headmaster's quarters and to the front door that led into the schoolyard. This entrance was never used by us, we went in and out by the back door at the other end of the building where it joined on to the music school where all the music parts were kept and where we held choir practice. Behind the music school a garden backed on to the house occupied by the Head's family.

The Headmaster at that time was the Rev. R.W.B. Langhorne, nicknamed 'The Guv', M.A. Priest Vicar of the Cathedral and a character of very large proportions. He stood 6ft tall, very upright, with hair brushed tightly back over his head, and a finely lined face. Dressed usually in his red cassock with a wide black leather belt at the waist and crepe soled black shoes. He was a most impressive figure, much admired, I understand, by the many little ladies who attended the Cathedral services, but to us very small boys a fairly fearsome figure. His family of four daughters and a son led a completely separate life from the school; one daughter, Judth, did feature in the summer in the school yard where, on a batting wicket with collapsible stumps, she would take part in cricket practice. She was a very fine bowler and batswoman and I believe went on to make quite a name for herself both at the Maynard School and afterwards. This was an inherited ability from her father who had been a fair cricketer in his time, playing for the Somerset Stagglers.

Cricket was therefore the important game at the Choir School [sic. Choristers' School] and a good cricketer was automatically a favourite of 'the Guv'. As teaching staff he was assisted by Mr Gandy Bradford and, (I think) Mr Treloar [ [there is a H.T. Treloar listed in the 1971 ECOCA list of members, and he was a chorister 1924-1928. If this is the same person, it suggests that older boys were teaching the younger ones, which would also apply to Eric Goldie, chorister 1919-1925, whom Denis goes on to mention]. Mr Bradford, whose boys were at the schoo,l was also the assistant organist. Another teacher, who was an ex-chorister, and lived in the school, was Eric Goldie; he had become a fine cricketer and was a protege of 'the Guv'. After leaving Exeter he became a professional singer and had a fine voice. Years later during the war, I attended a performance of Congreve's Love for Love at a London theatre and was intrigued when, in the interval, the audience was entertained to songs by Eric Goldie.

The Choir

This consisted, as I think it still does, of ten on Decani Side, and ten on Cantoris - I was a member of Cantoris and we considered ourselves much superior to Decani. In the front pew above the choir beyond the Bishop's Throne sat the probationers. It was the responsibility of certain boys to set out the music for the following day's services, and I still recall a dark afternoon on returning to school, having collected twenty sets of the next day's music from the practice school cupboards, and also the key to the Great West Door of the Cathedral, starting with another small boy across the lamp-lit Close to the West Door opposite St. Mary Major's [i.e. to the Great West Door. Unexpected that choristers would come and go via that door, rather than the North Porch, which would have been almost directly opposite the alleyway to the school. St Mary Major was demolished in 1971]. Inside, we locked ourselves in, and made our way up the Aisle of the Nave to the side aisle under the South Tower where all the light switches were situated. [he means the South Transept, where the light switches in fact are still located] We turned on one light in the Choir and the light over the Organ Loft. Having set out the music we climbed the steps under the screen into the organ loft. There was no one to worry about, no one to tell us not to, so we then switched on the organ and sat side by side and made the most wonderful noises with it. It was marvellous to be able to produce great gasping deep notes from the 40 pipes in the south aisle, and pull out the so much despised Vox Humana stop. If we stopped to think and listen it was then that we began to feel the age of the building around us, the strange sounds we thought we heard, and the strange figures we thought we saw in the shadows of this great Norman edifice. This was enough, switch off everything and rush down the stairs and along the nave and out through the West Door. Close it fast and turn the massive key. So we would hurry back across the Close and into school, puffing and blowing. [It is hard to believe now, that two unaccompanied choristers did this duty as a matter of course!]

Names remembered

[They are rearranged here into alphabetical order and presented as a bulleted list - they are in continuous text in the original. Extra information has been added between [ ] from ECOCA lists of members from the 1960s and early 1970s - kept in the Cathedral Archive]:

- Banner & Banner, brothers from Mufulira in Northern Rhodesia [now Zambia]. Their father was a gold miner

- Bingham, John, from Plymouth, who later rowed for Oxford, and appeared on T.V. on a Sunday interview of a [Bingham, J. 1927-1932]

- Clotworthy, from Helston [Clotworthy, W.J. 1927-1933. His address at that time was in a house amusingly (and perhaps also appropriately?) called 'Perfect Pitch'. One ECOCA list also has him as Clotworthy, H.]

- Collins

- Cotton, Frank, from Bradford [1926-1931. A leading founding member of ECOCA in the mid-1960s]

- Gibson, Rex. Had a lovely voice

- Gladwell

- Goldsworthy

- Hazelgrave, from Yorkshire [ECOCA lists have him as Haselgrave, N.C. and once as Haselgrove, N.C., from Leeds, 1925-1931]

- Hibberd, from Exeter [Hibberd, John 1923-1927]

- Hurren [Hurran, W.J. 1921-1928.]

- Moore

- Peace, from London. Now lives in Plymouth I believe [Peace, J. 1924-1931, and with an address in Plymouth, as Denis thought]

- Spiller, Joe [Spiller, J.L. 1923-1928]

- Stilliard, from Launceston [Stilliard, A.M. 1924-1929]

- Vercoe from Plymouth [the website of the bibliography says that Denis had an elder brother, Arthur Guy (1906-1954), so presumably Denis is referring to him, but odd that he does not say he is his brother. Denis also had an elder sister, Valentine Edith Barbara (1913-1994)].

- Williams, F.J., from Plymouth, who became a Hospital Secretary

- Williams, Roderick

Hobbies

In the Head's garden there was a large Mulberry tree and as the leaves were the staple food of the silkworm, someone started keeping them; I don't know who it was, but the craze soon spread, and many of us had our boxes and tins, lined with mulberry leaves, in which our munching silkworms lived and seemed to thrive. Finally they made their wonderful cocoons of golden silk and then everyone had their winding spools made of cotton reels and soon there was any amount of lovely silk. As I remember, this craze was fairly short-lived and I think it was just a 'once off'.

Another short craze that occupied everyone for a time was the cutting out and polishing of shields and plaques from coconut shells. We cut them out with penknives and polished them with shoe polish, and I recall they looked very good.

During one holiday, John Bingham and I were taken to the Theatre Royal in Plymouth to see R.C. Sherrifs play Journeys End. I think it must have been a summer holiday, as during the following term, in the dark wet evenings after tea, John Bingham and I decided to present our own production of Journeys End for the benefit of the rest of the school and any staff who cared to attend. We had no script and very little scenery. Undeterred, we managed to create a First World War dugout from desks, blankets etc and a large metal folding screen. We both knew most of the words of the play, or a resume of them, and were quite able to invent others as we went along. I played the part of Stanhope, the hard-drinking, hard-swearing Captain, and John Bingham played the gentler character Raleigh who thought Stanhope was marvellous. The play was an enormous success. In the original stage production the play finishes when a direct hit destroys the dug out completely. Our production finished in a blaze of lights flicked on and off to represent gunfire and the frightful crash of the great metal screen fell on to the floor, narrowly missing the recumbent Raleigh. When the lights came on, we received hearty congratulations from 'the Guv' whose only adverse comment was on the non-stop flow of bad language Stanhope managed to put into the script. This was obviously something that had made a deep impression when I saw the play at the Theatre Royal. We did one other play, but for the life of me I can't remember what it was called.

Teaching

As a little newcomer, I was in a class taught by Eric Goldie and Mr Treloar. I can remember little about that time so it made little impression. Later I moved into the upper class where the principal teaching was done by 'the Guv'. His great sublect was Latin and we spent a lot of time on this subject. We were taught a lot of the basics by rote, reciting such things as the pronouns quim, quae, quod in rather the same way as we used to learn our tables, parrot fashion, when at one infant school. I particularly remember the quim, quae, quod as I had failed with some others to learn it in time for the classroom and we were told we were to report to 'the Guv's' study, that evening, word perfect, or be beaten. When that time came, we were lined up and to the time of a metronome, which swung and ticked in front of us, we had to recite our piece. This system of learning was so effective that I can still shut my eyes and reel it off as if I had just learnt it.

'The Guv's beatings were a terrifying occasion as we were beaten with a mahogany clothes brush, stretched out on his leather covered sofa, with our trousers down, and our head buried in a cushion to muffle our howls. I must say it was a reasonable deterrent!

The teaching of other subjects was minimal - I imagine we learned some English and History and Geography but can recall no such classes. Maths was taught by a Mr Treloar, a nice man but quite unable to teach - as a result when I left and for ever after, Maths remained a mysterious and impossible subject as far a I was concerned.

More about schooldays

The time given to classes was fairly limited as we had Mattins each morning, at I think 10.30 and Evensong each afternoon at 3 p.m. Choir practice had to be fitted into each day in the early evening I think. Under the present education system I don't think our regime would have been tolerated. Our main job in life was to be a good choir, and a lot of time was spent to that end.

Every Saturday morning a test was held in which we all had to take part; this was called 'collections' as the questions on the paper covered all the work done during the week. This was a much feared test as failure to achieve a certain percentage of correct answers could mean a visit to 'the Guv's' study to be beaten. Looking back, fear of 'the Guv' ruled a lot of our actions, but at the same time he could be kind and entertaining.

There was a period when on Sunday evenings we were invited to gather in his study where we sat wherever we could, to hear him reading to us. I can still remember the title of a most exciting book he read called Hispaniola Plate; who it was by I don't know, but it was a jolly good story. ['The Hispaniola Plate (1683-1893)' was a historical novel written in the late 19th century by John Edward Bloundelle-Burton. No wonder Denis liked it, as it revolves around the legendary Captain Sir William Phips and Lieutenant Nicholas Crafer as they embark on a treasure-hunting expedition in the West Indies.]

After all these years I remember a certain Saturday 'collection' at which in one question we were asked to write down titles of books by Robert Louis Stephenston. As well as the better known ones, I included The Island Nights Entertainments. When the paper was marked I was infuriated on being told by Guv that there was no such book; and he refused to accept my assurance that in fact I had the book at home. [Denis was correct. The book was published by Stephenson in 1893, and was one of his last completed works before he died in 1894.] Had I pressed the claim I might well have ended up face down on the sofa. However, on the whole he was a fair man.

In connection with the weekly 'collections' I remember also an occasion when Eric Goldie promised to take the boy with the highest mark to the cricket match to be played against St Peter's School at Exmouth that afternoon, on the back of his very powerful motor bike, and by a supreme effort I won.

Pocket Money

As a junior our pocket money, issued each Wednesday, was 3d. [modern 1.25 pence] and as a senior 6d [modern 2.5 pence]. We were allowed to go into town with our pocket money and visit Freeths, a marvellous sweet shop in the High Street. We broke our money down into halfpennies and came back to school with, as a junior, six bags of sweets, and 12 as a senior.

Greedy boys, like me tended to quietly eat the lot during the afternoon whereas there were more careful types who could spread out their sweet ration over several days, if the others didn't manage to raid their carefully hidden treasure.

Sport

As I said earlier, the most important game played was cricket. We had no playing fields of our own and all practice took place in the School Yard on a coir-matting pitch with stumps on a hinged base and nets round the batting end.

On Wednesday afternoons and on Sunday afternoons, weather permitting, we went by bike or on foot to the Wonford Mental asylum on the outskirts of Exeter where we had permission to play cricket on their playing ground. [this is in the Heavitree part of Exeter, and is now the area of the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital. Eric Dare's memoirs also mention this]. It was a strange experience, as around the playing ground there was a tar macadum path and here there would be parties of the inmates being exercised by the staff and as a lot of them were fairly unstable to say the least of it, their audible shouted comments and strange behaviour tended to be a distracting feature of our afternoon's cricket. I believe at that time it was a very expensive private asylum. We must have been strangely insensitive, or perhaps this was the way mental illness was treated, but their behaviour didn't worry us at all and was far more a reason for mockery - very bad behaviour for what were supposed to be a lot of Christian young gentlemen.

In the winter and Easter terms we played football but where our ground was I can't remember. A goal was painted in white on the wall at each end of the school yard for us to play amongst ourselves. I remember little about our football except for a boy who was there with me called John Peace who used to telll us that his greatest ambition was to play in Goal for Arsenal - he lived in London I remember. He was a good goal keeper and kept Goal for the whole term.

Another game we sometimes played, but not often, was bowls on the lawn at the Archdeacon of Exeter's house near the school (now an office) [the large building on the northern side of The Close, on the opposite side of the street from the current Hall House of Exeter Cathedral School]. He was called [William] Surtees, and later became I think, Bishop of Crediton [Archdeacon of Exeter, 1925-1930; Bishop of Crediton 1930-1954. There is a photo of him in this archive.] - he was a fine man and much liked and admired by the boys. Later when I was at Exeter School he confirmed me.

Also in the summer we went for swimming, again by bike, to a boys reformatory at Whipton near Exeter on the road to Broadclyst. [This was originally called The Devon and Exeter Reformatory Farm School for Boys. It had been established in 1855 and moved to the location on Beacon Road to which Denis is referring, in 1900. It became an Approved School and closed in 1955.] I remember the water was always a murky greenish brown and tasted horrible. We were always intrigued by all the writing on the walls of the changing shelters beside the pool - names of delinquent boys with the length of their sentence and with some very terse comments on the staff in charge of them. There was a high fence around the pool so no costumes were worn.

Health

The Matron, a short fat bespectacled dame, whose name I can't remember, greatly admired 'the Guv', and I imagine disliked us intensley. I think the feeling was reciprocated. Her panacea for all ills was a glass of castor oil with some orange juice floating on top it - revolting. For years I couldn't stand orange juice because of it.

Also, once each week, when we came down to the dining room for tea, instead of empty cups and saucers by our places which we could take ourselves to be filled from the tea urn, inside each place would be a half-filled cup of grey looking tea. Staff and Matron would be gathered round with strict looking faces and we were instructed to drink this down before we started tea proper. This was the weekly dose of Epsom Salts! I'm sure it was good for us but how we hated it.

I remember John Bingham contracted mumps and swelled up enormously. As I was in the next bed to him, it was decided that I was a certain starter, so we were despatched to the Digby Isolation Hospital (now an ordinary hospital I believe) [it ceased being a hospital in 1986, and was converted into residential appartments] where we stayed for about two weeks.

One of the biggest medical scares arose one term when a boy developed diptheria, in those days a 'killer'. Immediately the doctors were called in and swabs were taken from all the boys and staff. The following day we were all assembled in the school yard and the Guv came out on to the top of the staircase in front of his door with a list in his hand. This was the result of the swab tests. All those whose swabs were positive were smartly chased up to a dormonitory upstairs and all the lucky negative swab owners were handed their fares to home and told to get going. I think we had an unexpected 3 week holiday that time. I think that there were only about 3 or 4 positive swab boys - and none of them developed serious diptheria. It really was a frightening illness in those days and deaths were common.

Dean & Chapter & Top Clerics

The Bishop of Exeter when I was a Chorister was Bishop William Cecil, he was the last member of the great Cecil family. Known to all the boys as 'Hairy Bill' he was a fine looking old boy with long white hair and beard. He rode a marvellous old green bicycle with straight handlebars. The story went that being so absent-minded, he frequently stopped to ask policemen in which direction he was travelling so that he could work out where he was going - I imagine as a good Bishop, his mind was on higher things.

Once each year at Evensong, led by the senior Verger and his Chaplain, he would process along the front of Decani and Cantoris and bless each choir boy in turn with the words 'The Lord Bless you and keep You'. We looked forward keenly to this occasion as it was a wonderful excuse for teasing the old boy. In the Vestry where we assembled before service to put on our suplices and to make ourselves tidy, there were hair brushes and mirrors and tins of a particularly powerfully smelling brilliantine perfumed with lavender. On this afternoon, we all plastered our hair down with a thick layer of this grease and by the time the Bishop had blessed about six boys, laying his hands on their heads, he was dripping with grease. His Chaplain carried a white towel and wiped his hands for him. I think he must have been a good sport as this happened every year and there were never any dire repercussions for us.

The Dean in my day was Dean Gamble [Dean 1918-1931]. He was one of a pair of famous London preachers, and in the early part of this century when church-going was an important part of life of an average family, people in London could be heard discussing who they would go to hear preach on Sunday - Gamble or Gough.

I remember very little about him except that in 1928 when his daughter Anthea was married to Dudley Carew, a member of a leading Devon family, another chorister Roddy Williams and I were chosen as her train bearers. [Anthea Rosemary Gamble married Dudley Charles Carew. He was The Times cricket correspondent at the time. The Carews were a very long distinguished Devon family.] I think possibly the reason for choosing us was that we were very much of a size and age. We were dressed in our red cassocks with Elizabethan ruffs and black patent leather shoes with silver buckles. [Denis or Roddy can be clearly seen in the photo] These must have been hired as I don't remember them staying in my possession after it was all over. It was a very big fashionable wedding and the reception was held in the garden and house of the Dean opposite the West Door; I don't know whether this still is the Dean's house or whether it's now part of the school. [The Deanery moved to Number 10 The Close in the early 2000s. The Old Deanery now houses the offices of Exeter Diocese.] We continued to carry the bride's train in and out of the crowd at the reception, and were constantly plied with glasses of champagne by the guests. I remember very little about it but think we thoroughly enjoyed it all. Afterwards we were presented with a pair of cuff links each as a token. Unfortunately the marriage was far from a success and soon broke down and there was a divorce. I can still see the great green ring (an emerald I suppose) she wore on her finger which I heard later she lost on her honeymoon - a bad start.

Other Members of the Cathedral Clergy that I remember were Bishop Trefusis, the Bishop of Crediton - Surtees, the Archdeacon of Exeter, Canon MacLaren & the other Priest Vicar the Rev. R.W.B. Llewellyn; he came into our life at school as he was in charge of all the music.

The music was held in shelved cupboards in the music school [known as the Singing School] and working on a roster we had to issue the copies of music at practice time and in the cathedral itself. I can still remember on one occasion when thirty copies of a certain anthem were required and only twenty-nine copies could be found on the shelf. When I told Reggie Llewllyn he said "Well you are responsible for producing the correct number, and if you can't, undoubtedly you are in for a monumental beating from the Guv." I can still remember the hours spent searching through all the music shelves until I found it. As a little boy of 9 or 10 it was quite a responsibility.

There must have been many other members of the Cathedral Clergy, but unless their life actually impinged on ours they made little impression. For instance there was an Archdeacon of Totnes but I can remember nothing about him. R.W.B.L's [the Guv] gift to each boy when he left was a copy of Jacks Book of Knowledge.

Services

As I said before, we sang Mattins and Evensong each day, and Mattins on Sunday. Evensong was sung by the other choir of men and boys from Exeter [I am not sure what Dennis means about Sunday services. He may be confused about who sang what services on Sundays. The 'other choir' could be a reference to the Voluntary Choir, who used to sing a 6.30 Sunday evensong until the early 2000s. The Cathedral Choir sang a Sunday afternoon evensong at 3.00 pm as well as Mattins and Eucharist in the morning.].

These services were always held in the Quire, and usually attended by the same small congregation of elderly male and female residents of The Close.

At least twice each year we sang various oratorios. My favourite was Bach's Christmas Oratorio; in this on one occasion I sang an echo in one part, from the Minstrels' Gallery in the north wall of the nave. Another I always enjoyed was the Requiem by Brahms. For the oratorios, full rehearsals were held in the Cathedral with a large amateur orchestra and conducted by the organist, with the organ being played by his assistant.

In passing, when I first went to the Choir School the organist was Dr Ernest Bullock. On leaving Exeter he went on to become the organist at Westminster Abbey. His place was taken by Dr Thomas Armstrong. Later he became the Professor of Music at Glasgow University, and later still the Head of the Royal College of Music in London.

During the year there were a number of formal occasions such as the Assize Sundays when all the judges and other Officials such as the Lord Lieutenant processed into the Cathedral. We used to watch with awe these famous Law Lords. In those days before the time of T.V., the newspapers carried very full accounts of all the great trials in particular murder cases, and made a much deeper impression on us then as the outcome of these trials was frequently execution. One of the judges we saw was the famous Chief Justice Avery, who was known to everyone as the hanging judge. I can still see his unblinking heavily lined face looking out from beneath his full bottomed wig. The other judge I also recall, maybe because he looked so different, was the Lord Chief Justice, who had a round, most benevolent face. I expect in fact he was just as tough.

Bishop Grandisson Service

I can't swear to the actual truth of this story but here goes. An old iron chest was discovered somewhere in the Cathedral and when opened, the document it contained was the original copy of the setting for a special Christmas Service. I believe this chest still stands in the south aisle behind the Choir. Dr Armstrong took this music and made a new setting of it, and on Xmas Eve after a lot of practice, it was performed for the first time for many hundreds of years. In those days, we sang it in the Quire on a winter's afternoon just before Christmas. We had a boy called Rex Gibson with a beautiful voice and he appeared holding a candle at the high altar to sing the first lines, and the response was given by six other choristers, three on each side of the altar, all with candles. So the service went on, but with no processions or any of the ceremony that now takes place on Xmas Eve.

Records

During my time at Exeter we made two records with the Columbia record firm, for which we each received 10/-. I can only remember one side of one of the records, this was 'Oh Little town of Bethlehem' sung with a rather nice descant. On the other side was an Easter hymn but I can't remember which it was. Unfortunately my copy was lost in Plymouth during the war. I would like to be able to get another copy. [this recording is available in this archive]

[Dennis refers to 'two records'. Nothing is known about the second one. Perhaps he is confusing two recording sessions - for side one and for side two - on only one record.]

Extraneous Details

The High Altar Cross

We were told that the jewels which are included in the cross were left in her will by a lady who attended the Cathedral. [It had been donated in 1923 as a tribute to the then late Mary Lumley, sister of Lord Mamhead of Exeter and ancestor of actress Joanna Lumley. Joanna's brother was a chorister at the cathedral in the 1960s.] When the cross was first put in place on the altar it was decided that, in view of the value of the jewels [It had three circular diamond brooches affixed at different points, and a diamond tiara halfmoon shape in the centre], a watchman should be employed. The first man chosen entered the Cathedral before closing time on the first night and was then locked in as an extra security measure. Soon after darkness fell, someone outside the Cathedral heard frantic calling from inside and the sound of someone beating on the Great [West] door. The key was fetched and when the door was opened, a terrified watchman burst out and no money could get him to return to the job. A replacement was found but the same thing happened. After this, the Dean & Chapter decided that they would leave it to the Cathedral and all the Spirits of the past to protect the cross. As far as I know, there has never been any attempt to rob the Cathedral. [Sadly untrue - in 1950, the cross was stolen, and taken away in a stolen Rolls Royce (the police said it was probably the only car considered robust enough to carry the cross's immense weight and size), and recovered near Exeter shortly afterwards. No one was ever caught.The story is related in DevonLive and includes mention of Peggy Conway being invloved in its recovery. She and her husband were life-long active members of the Cathedral until they died in the 2020s.]

We were told that the jewels which are included in the cross were left in her will by a lady who attended the Cathedral. [It had been donated in 1923 as a tribute to the then late Mary Lumley, sister of Lord Mamhead of Exeter and ancestor of actress Joanna Lumley. Joanna's brother was a chorister at the cathedral in the 1960s.] When the cross was first put in place on the altar it was decided that, in view of the value of the jewels [It had three circular diamond brooches affixed at different points, and a diamond tiara halfmoon shape in the centre], a watchman should be employed. The first man chosen entered the Cathedral before closing time on the first night and was then locked in as an extra security measure. Soon after darkness fell, someone outside the Cathedral heard frantic calling from inside and the sound of someone beating on the Great [West] door. The key was fetched and when the door was opened, a terrified watchman burst out and no money could get him to return to the job. A replacement was found but the same thing happened. After this, the Dean & Chapter decided that they would leave it to the Cathedral and all the Spirits of the past to protect the cross. As far as I know, there has never been any attempt to rob the Cathedral. [Sadly untrue - in 1950, the cross was stolen, and taken away in a stolen Rolls Royce (the police said it was probably the only car considered robust enough to carry the cross's immense weight and size), and recovered near Exeter shortly afterwards. No one was ever caught.The story is related in DevonLive and includes mention of Peggy Conway being invloved in its recovery. She and her husband were life-long active members of the Cathedral until they died in the 2020s.]

There also used to be some story about an ancient ring which was placed between the leaves of an illustrated missal in the Cathedral and when next the missal was opened the ring would have moved within the book.

Each member of the choir [i.e. chorister], when he was installed, began reading the Bible at the beginning, and continued to read through his career during the first and second lessons, trying to read the complete Bible during his time as a chorister.

Installation of a Probationer as Chorister

When a member of the choir [i.e. chorister] left, his place would be filled by one of the probationers, according to seniority. This was a very important day in a small boy's life - and the senior choristers made very sure he would never forget it. He was told that, on the day of his installation, which took place at the first possible evensong following the vacancy, he would be left in the small chapel in the South Transept for the first part of the service and he should spend that time on his knees in prayer. When the time came for his installation, which came at the end of evensong, the senior Verger would come for him, but before taking him into the choir would brand him with his silver wand suitably heated, on his bare bottom. When therefore he heard the Verger approaching he should have prepared himself with his trousers down. You may laugh now, but to a small fry [boy] this was a very awe-inspiring occasion and I can still remember how terrified I was when I heard the verger approaching. I can't remember how prepared I was, but it must have been an enormous relief when he merely led me into the quire to be installed.

School Food

As far as I remember, on the whole the food was good. When I was at school, the cook was called Beattie. The only thing I remember about her was that she had a white cat and whether true or not, it was popularly believed that all white cats were stone deaf; in fact "Beatties Pussy", as it was known, really was deaf. It was much disliked as it was obviously allowed free access to the kitchen as we would frequently find white hairs in our food. It was recognised practice to kick this cat if you could creep up on it in the passages. I'm sure Beattie loathed us all.

I remember very little about the meals except how much we used to look forward to breakfast on Sundays, when we got sausages. I think we stuck to a rigid weekly menu of roast on Sunday, cold on Monday, hash on Tuesday and then boiled beef and carrots and an enormous boiled onion on Wednesday, cold meat on Thursday, fish on Friday and a made up meal on Saturday. I've never forgotten the Wednesday meal, as I detested onions and refused to eat them, and I was told to sit at the table until I had eaten it. As I was still there when it came time to go to evensong, I was released with all sorts of dire threats attached. However, ever afterwards I made sure I had a large envelope with me in which I put the beastly onion and later dumped it down the lavatory.

In the evening we used to be given a milky drink before going to bed, and one of these over which I had trouble was chopped up onions in hot milk - however I won through, though I can't remember how. In all the 45 years of my marriage we have never had an onion in the house!.

Xmas Parties

I wonder if holiday arrangements for choristers remain the same as they were when I was at Exeter?

Our Christmas holiday began some time soon after the end of the first week in January; this, oddly enough, gave us a rather superior edge on our non-chorister friends who were at home for Christmas and went back to school for the Easter Term two weeks, at least, ahead of us. As far as I remember we experienced no deprived feelings at being stuck at school when all our non-singing friends were already at home on holiday. When we finally did get home we were able to boast so loudly of the wonderful parties we had had at Exeter over the Christmas period that many of our friends were undoubtedly extremely jealous of us. Of course there was always a school party held at the school and much enjoyed by everybody.

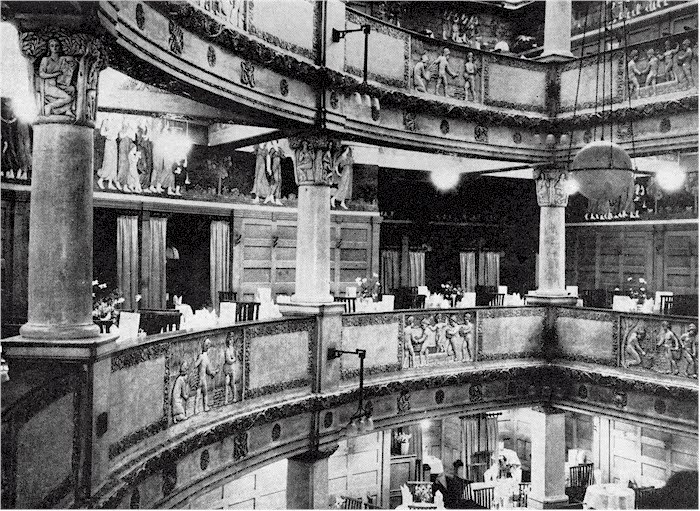

Most of the senior members of the Cathedral Chapter obviously felt compelled to lay on a party for the choir each Xmas. I imagine this had become a tradition and no party giver liked to break it. In those days on the Corner of Bedford Street where it abutted on the High Street, stood Deller's Cafe. [Sadly destroyed by bombing in 1942] Here it was that the wonderful gorging Christmas parties were held. It was really just a glorious feed with masses of cream cakes and other goodies stacked on the tables for us to tuck into. I don't remember much in the way of party games or anything like that. We used to go straight from Evensong across the darkened Close to the lovely food paradise of Deller's and spend a couple of hours making beasts of ourselves.

Most of the senior members of the Cathedral Chapter obviously felt compelled to lay on a party for the choir each Xmas. I imagine this had become a tradition and no party giver liked to break it. In those days on the Corner of Bedford Street where it abutted on the High Street, stood Deller's Cafe. [Sadly destroyed by bombing in 1942] Here it was that the wonderful gorging Christmas parties were held. It was really just a glorious feed with masses of cream cakes and other goodies stacked on the tables for us to tuck into. I don't remember much in the way of party games or anything like that. We used to go straight from Evensong across the darkened Close to the lovely food paradise of Deller's and spend a couple of hours making beasts of ourselves.

There used to be three or four of these parties during the Xmas period. One of the best on tap at this time was the night when we were all taken to the Pantomime at the Exeter Theatre, and back to school afterwards for hot drinks and mince pies.

During 1928 the Guv was involved in all the planning and production of The Book of Common Prayer with the Additions and Deviations proposed in 1928. In July 1927 a Measure was passed in the Church Assembley for the purpose of authorizing the use of a Prayer Book which had been deposited with the Clerk of the Parliament, and was referred to in the Measure as "The Deposited Book. The Measure and the Book had been previously approved by large majorities in the Convocation of Canterbury and York. A resolution under the Church of England Assembly (Powers) Act 1919, directing that the Measure be presented to His Majesty, was afterwards passed in the House of Lords by a large majority. But a similar resolution in the House of Commons was defeated on the 15th December 1927, and the prayer book of 1927, therefore, could not be presented for the Royal Assent. Early in 1928 a second Measure (known as the Prayer Book Measure, 1928) was introduced in the Church Assembly, proposing to authorize the use of the Deposited Book with certain amendments thereto, which were set out in a Schedule to the Measure. This Measure was again approved by large majorities in the Convocation and the Church Assembly; but a resolution directing it should be presented to His Majesty was defeated in the House of Commons 14th June 1928. If the Prayer Book Measure, 1928 had received the Royal Assent the following would have been printed as the title of the new Prayer Book. "The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and other rites and ceremonies of the Church according to the use of the Church of England together with the form of Making, Ordaining and Consecrating of Bishops, Priests and Deacons. The Book of 1662 with Additions and Deviations approved in 1928". As a result of the Guv's personal involvement we all bought copies of this book.

[When the 1928 Prayer Book was introduced at Exeter, it was not well-received by everyone. The League of Loyal Churchmen demonstrated against it in 1930 by processing through Exeter. The procession ended with delivering a protest to the Deanery and then burning a copy of the book outside the cathedral. Several local and national newspapers ran this story:

Photo: An unidentified newspaper cutting. A very similar photo was published by The Western Morning News, 20th January 1930; their article included a photo of the actual burning - article as pdf, source, British Newspaper Library.]

Dormitory Story Teller

At night, when lights were out in our dormitories and before sleep caught up with us, was the story-telling time. There was always someone who had a good story to tell and I had had a marvellous grounding in this. All through our childhood from the time we were able to take in a story, during the winter evenings when tea was over, we would all gather round the fire in the drawing room and father would fetch down from the shelves a bound volume of the Boys Own Paper. We must have had a dozen or more volumes going back to as early as 1887. I still have about five of them including this very early one, and I see included in that volume what was I suppose one of the most famous school stories ever written 'The Fifth Form at St. Dominics' by Talbot Baynes Reed. It is interesting to browse through these old books and see how many authors later to become famous were already writing boys stories for the B.O.P.; in their 1888 Volume there is a very early story by Conan Doyle, written before he created Sherlock Holmes.

The following is a list of those wonderful stories which I retold night after night during the time I was at the Choir School. It would be interesting if any old choristers of the same vintage can still remember any of these. In the Land of Shame by Major Charles Gilson. Into the Forbidden Land by Raymond Raife. Kookaburra Jack by Argyll Saxby. Treasure of Kings by Gilson. The Mystery of Ah Jim by ? [Captain Charles Gilson]. Jack Without a Roof by Gilson. These were all very thrilling stories that made excellent Dormitory re-telling.

I'm sure there are all sorts of interesting details of my time at Exeter that I have omitted, but you must take into account how long ago it all was and forgive these omissions."

Sources include

Denis Leplastrier Vercoe - WikiTree - https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Vercoe-474 (accessed October 2025). Reproduced with permission of Paul Stephens

Devon Heritage - The Devon and Exeter Reformatory School for Boys (accessed November 2025)

Exeter Memories - Anthea Gamble wedding 1928 photo and comments - (accessed November 1928)

Demolition Exeter - Deller's Cafe (accessed November 2025)