MY LIFE

Eric William Soundy Dare

(1927-2021)

Exeter Chorister 1937-1942

Edited by Mike Dobson

Editorial

|

Photograph of the front cover of Eric's 111 page printed 2020 autobiogrpahy. |

Eric completed his autobiography in the year before he died, in July 2020. Part Two is about his time as a chorister at Exeter Cathedral, and is the section presented here. The autobiography before this is about his family and early years. The sections afterwards are about his schooling at Blundell's in Tiverton and his adult life.

The printed version of the autobiography had footnotes. I have placed these below the paragraph from which they are called.

Editorial changes are mainly to correct the very few typing errors. Some explanations have been added to aid the reader; these and other editorial comments are shown between [ ] brackets.

Eric has this note about the photographs of the school and choristers dating to the late 1930s and early 1940s, several of which were included in the printed version of his memoirs and are included in this web version:

In the autumn of 2007 photographs had been found of the old Choristers' School and given to the local BBC TV 'Spotlight' who showed a couple of them. The presenter, whom I knew when we were both at Radio Cornwall, asked who the boys were and the name of the photographer. Since one was of me and another chorister with an enormous model of the Eiffel Tower from the Meccano set, I was able to supply the information; (the photos were taken by the young assistant master, Keith Gibb). This led to a short recorded interview that went out on the programme a few days later. The photographer's widow [she was actually Keith Gibb’s daughter, whom I met in 2015 at her home in Topsham, to talk about the photos] heard of this and contacted me. By a strange coincidence she had married a boy I shared a study with at Blundell's. From the album that she had retrieved from the BBC, I was able to take copies of several photos. [The album is still in her possession]

Many more of these photographs can be seen in the ECOCA gallery for the 1940s.

Mike Dobson, Exeter, December 2022

Preface to these Memories

Growing old - it's not nice, but it's interesting August Strindberg

1997 marked a milestone for me when I reached my seventieth birthday. But 1998 has perhaps even greater significance when the last two members of my parents' generation died: Frank Soundy, one of my mother's younger brothers, died in January just before his 94th birthday, and in March the husband of my father's cousin, Ron Lawrence, also died, aged 89. I became very much aware that I was now the eldest in the family and recalled a poem from one of the 'O' level set books that had always impressed me:

The fools, my juniors by a year,

Are tortured with suspense and fear;

Who wisely thought my age a screen,

When death approached, to stand between:

The screen removed, their hearts are trembling;

They mourn for me without dissembling.Jonathan Swift: Verses on the Death of Dr Swift

Not that my heart has been 'trembling' or that, at this time, I have a fear of death, but I am conscious that an era has passed. Often, I have regretted that I didn't ask more questions of my parents, grandparents and their contemporaries. Now there is no-one left who could confirm or refresh my memory[1]. But in response to a request made some years ago by Susan, I was prompted to make a start on recording memories that might be of interest to succeeding generations. I feel I have been very lucky over all, and my journey has been different from many others'. In my early years I was continually breaking new ground in both families: I was the first to go to a 'prep' school (itself a rare sort of school); the first to go to a public school; the first to go to a university[2]; and the only one of my generation to join the services at the end of the 1939-45 war -and certainly, no one else had won two prizes before their first birthday!

Note 1. “...that fragmented vision of elsewhere with which each of us lives." Penelope Lively |

Note 2. My mother and her elder sister, as well as their mother, all attended a teachers' training college. |

I began this in November 1998 with some enthusiasm, but then abandoned it half way through. In part this was through a reluctance to write about the difficult period in my early life. But from time to time, more particularly in recent years, as I have reached my nineties I have been more focused. It is a relief that I have at last got there, although it has taken more pages than I ever expected, especially with the inclusion of photos.

July 2020

PART II: ALL CHANGE

A Memorable Year

|

Studio portrait of Eric, in Cathedral school uniform, with younger brother Roderick, during Christmas holiday(?) 1937. Eric Dare archive. |

In the Spring of 1937, Dad took me to Exeter for a voice trial. I can't remember whether l was told what the future might be if I passed - I doubt if my parents knew themselves. I imagine that someone like Mr Pullein, the organist/choirmaster of St Mary's church in Calne (family home in Wiltshire) or my piano teacher, Mr Freeth, sowed the seed. All I know is that when I went for my piano lessons I was prepared for simple voice tests and was given a book of vocal exercises to practise. Mother was at home with Roderick, so grandma Soundy accompanied my father and me to Exeter Cathedral Choristers' School. In the headmaster's study I was presented with a passage to read and then in the singing room I sang a verse of a hymn ('There is a green hill', I think,) and picked out the different notes of a triad. I might have also sung some scales. And that was the test! I was to join the school in September.

The three of us then went to the school's tailors, Whippell's in Exeter High Street, my new school uniform was purchased including a grey suit, Eton suit, collarless shirts, separate soft and stiff Eton collars - and a mortarboard! Besides all the obvious clothes, there would be sheets, pillowcases and towels. I don't doubt that Grandma Soundy paid for a lot of this - I can't imagine my own parents finding so much money. Before joining the school, Mother sewed Cashes labels on all my clothes, and a trunk and a tuckbox had also to be bought. We had been advised that it would be a good idea for me to make a start on learning Latin. Someone in Calne produced a rather hefty book with the instruction to start learning 'mensa' for the first declension. I didn't get far and no one explained to me why in Latin 'table' needed so many different endings.

During the six months before I left home, I was given some homely instruction such as accepted table manners, e.g. how to eat soup, the proper way to hold a knife, fork and spoon, (not grasping the handle with the whole hand!), keeping one's mouth closed when eating - none of these niceties were particularly practised, especially by Dad! My speech also had to be reformed. I remember vividly when I had been playing with a toy garage with a neighbour's daughter who had the 'U' pronunciation, but, imitating my father, saying 'garridge'. It was Dad who corrected me!

School fees at Exeter Cathedral Choristers School were £15 per term - reducing to only £5 when a boy was made a full chorister. This should have been warning enough of the quality of care and education I might receive, but I am sure that the whole family was proud that I was breaking new ground.

I must have made my first solo train journey, (the first of scores subsequently,) getting to Exeter on a Friday to spend the night at Uncle Frank's and Auntie Nell's. They had undertaken to get me to the school the following day. After lunch I went to the bedroom to change into my school uniform. My first problem was actually putting my (soft) shirt collar onto the shirt with studs. Did the collar go outside the shirt or inside? I knew a little about studs since we wore stiff collars in St Mary's church choir and I experimented, now with a soft collar. Eventually I reasoned that the collar would look neater if it was attached, from the neck: stud-collar-shirt. Wrong!

But such dilemmas and difficulties with no one to help and advise were just the start of the most wretched period of my life. Into the Cathedral Close, up an alleyway, and Uncle and I were in the walled playground with the gaunt school building on the right. Elegant and wide steps, with a curving handrail on each side, took you to the front door leading to the headmaster's study. Here I was handed over to the Head, the Rev'd RWB Langhorne, always referred to as 'Guv'.

|

Dr Wilcock 'baldie' in his regular wear - rather 'dapper'. Keith Gibb archive. |

|

Steps at front of Choristers School, not for boys' use! Kitchen and maids in the basement, School rooms, above; dormitories at the top Keith Gibb archive. |

My First Term

Although I suppose I had some feelings about leaving home, I don't remember being especially anxious or excited. (Was this when I first developed a phlegmatic attitude?) I had experienced occasional changes in routine (having a baby brother, for instance), but, aged 9+, I did as I was told and accepted that what was being arranged by my parents was in my best interests. Nothing could have prepared me for such an almighty shock!

The school building was very old (18th century?). For the boys' daily use there were two common rooms, the smaller of which was for the senior boys only. The larger, for the rest, had open lockers under the two large windows that overlooked the playground (and entrance) and two large tables. A wooden barrier separated our side from a full-sized billiard table that senior boys were occasionally allowed to use, but it was out of bounds for most of us except to practise on one of the school's pianos. On Sundays our new starched Eton collars were placed on the (covered) billiard table. Another piano was in a much smaller room, converted shortly after my arrival into a 'Prayer Room' with coconut matting on the floor, a lectern, and chairs in rows where we had prayers at the end of the day and where Miss Reader, the visiting piano teacher, who also taught French, gave her lessons.

Upstairs there were four dormitories with iron bedsteads. Each has a red/black striped blanket and counterpane, (no eiderdown) and I was often cold. There was a chair by each bed for our clothes. Cabinets in the centre held spare clothes, etc., and on top, a bowl filled each night with (cold) water for washing and teeth cleaning. At one end of the corridor was a large bathroom with water-proof flooring and two baths. Every morning they were filled with cold water and each boy took a (hurried!) dip; hot water in the evening once a week for better bathing. A door at the other end of the corridor led to the bedroom of 'Nurse' Harper, the unfriendly matron, (a 'dragon') and to the headmaster's bedroom and other stairs to the ground floor where Matron had her private room next to Guv's study.

At one end of the main corridor, separating the two general rooms, were steps that, on the left, led to a way out to the boot room; on the right to the basement where were the kitchen, the maids' quarters and the boys' entrance to the dining room. Adults used some other steps, near Nurse's room, to reach the dining room. This had been built (in 1900?) and joined the school to 'Abbot's Lodge', one of the oldest buildings in the city. This was the Headmaster's house where the rest of his family lived.[3]

Note 3. Guv had, apparently, a record of an Abbot's feast being held there in 1216. It was demolished when a German bomb fell on it and the school in May 1942 |

When I was there, we rarely saw the eldest of the Headmaster’s children, Edward, as he was Headmaster of Dean Close (prep) school in Cheltenham. The daughters lived there with their mother, a tall elegant, softly spoken lady. The daughter Eleanor was a particular beauty whose marriage in the cathedral took place while I was a chorister; Mary was an artist and Ruth was a county cricketer. The youngest was Janet, (about 21?), who spent a lot of time with Matron in her room, behind the Headmaster's study, and began to learn to play the organ in the cathedral at the same time that I did. When she used the organ in the rehearsal room, she gave us 1/2d to pump for half an hour! Soon after I left, she also married.

There were three other adjacent buildings. The rehearsal room was reached by going up a flight of stone steps above the boot room. Here there was a baby grand piano, singing desks, and a hand-pumped organ. To the rear of the boot room was a 'modern' classroom built with wooden frames and walls (using asbestos(?)). It was divided into two classrooms by sliding doors (opened for the Christmas party.)

|

Steps leading to the rehearsal room. Below, the boot room (outdoor shoes, football boots &c) and loos: urinal wall and four(?) cubicles.) Keith Gibb archive. |

|

Abbot's Lodge, one of the oldest buildings in the city Keith Gibb archive. |

I was one of three new boys. The other two probationers were David Sayers from Wales, who emerged years later at an Old Choristers’ reunion and subsequently became its chairman for a period, and Christopher Harding whose father was a vicar in Lapford, Devon. He was a tall gangling boy with glasses whose walk was a sort of glide and (inevitably) was nicknamed 'Ghost'.[4] He was teased and bullied mercilessly. (He became a BBC engineer and I made surprising contact with him years later through MRA. He died from cancer in his fifties.)

Note 4. We all had nicknames: such as 'Squeaker', 'Skinny' and 'Toffy' - mine was 'Specs', though I wore no glasses! Perhaps I was considered brainy! |

I don't know whether I sobbed that first night, full of foreboding, abandoned and loveless, in cold sheets and a blanket that added little warmth. It wasn't the first time I had slept away from home, but previously I was always comfortable and felt secure. This was the first of my 'character-moulding' experiences.

There were some horrible boys in the school. One such, a probationer named 'Hall', celebrated our arrival (and his return to school) the next morning by leaping from his bed in the corner across all other six beds in the row, trouserless and peeing at the same time. He paid particular attention to poor Christopher. Later, he was withdrawn from the school. We didn't know why.

On weekdays, after the cold bath, washing in one's bowl of (cold) water on the locker and getting dressed, we had half an hour 'prep' before breakfast. One could tell the day of the week by the breakfast and lunch menus. Two I particularly disliked: cold mackerel soused in vinegar for Wednesday breakfast - we could smell the vinegar on Tuesday evenings - and Saturday lunch of rice pudding preceded by stewed rabbit. Nurse Harper would wander between the two tables with their bench seats urging you to 'eat it all up'. “But that's all black,” I would protest. “That's only blood where it was shot!” She was equally unsympathetic to the large gobbets of gristly fat. She would lean over you, almost submerging your head in her large bosom, to cut it up. “Now you can eat it!”

The daily routine after breakfast, in varying sequence, included lessons; medication (a dose of quinine, or antiseptic gargle that de-sensitised one's tongue and throat, or iodine on a lump of sugar following the outbreak of polio; break; Matins in the cathedral; choir practice with the Organist (Music Director), Dr Wilcock ('Baldie') in the song school (on Thursdays with the men), more lessons, Evensong, tea, practising the next day's pointing for the Psalms with the sub-organist, Mr Hinds,[5] and prep. There were breaks for play and for piano (organ) practice.

Note 5. He left soon after war was declared in 1939 and never returned. From then on there was no regular sub-organist. |

On Wednesdays there were no sung services and we had lessons only in the morning. After lunch on Saturdays we would be given pocket money for sweets - 3d for probationers, 6d for choristers, 9d for seniors. Chidgey's in North Street was our 'tuckshop'. Though occasionally we would go to Ferrises (?) in Paris Street for Cadbury's 2d chocolate bars filled with caramel, Turkish delight, peppermint, etc. On Wednesday afternoons we went to a sports field for soccer or cricket. On Saturdays we had lessons in the morning and were free after lunch until Evensong at 3 p.m. On Sundays, dressed in our

Eton suits, there was Matins followed by Sung Communion every other week and Evensong at 3 p.m. in the summer the choristers processed out of the cathedral before the sermon to get away for an extra period of cricket. On Saturday evenings, instead of prep we would be at our desks to write our weekly letter home. The envelope had to be left open and handed to the Matron - which severely limited what we might have wished to say. In the two choristers' classrooms we took down the weekly form order to enclose with our letters. How these figures were arrived at, heaven only knows.

Our parents were invited to pay for a weekly comic or paper for their sons. I had never had a comic in Calne, but while others had Hotspur or Tiger Tim, mine elected Arthur Mee's Children's Newspaper! No one wanted to swap with me - though maybe that was one reason I got the nickname 'Specs'. My one chance during that first term to read the comics came on Sundays when the choristers were at Communion and the probationers, who otherwise attended all other services, came back to the school. A chance to look at other choristers' comics from their open lockers!

The probationers' teacher was Mrs Treneer. I was quite bright and had no problem with the run-of-the-mill lessons, but her attempts at teaching (and speaking) French were abysmal. I doubt she had had any contact with real French. She was able to supervise a start to my learning Latin.

I had been given the stick, I believe, at Calne Junior School, and was 'given the ruler' on my hand at Guthrie Infants (in Calne); the punishment at Exeter was a long-handled clothes brush on the bare bottom as you lay trouserless on the sofa of Guv's study, his left hand on your neck as he administered (usually) three strokes with the brush. This was given if you accumulated three 'black marks' noted in his black, loose-leaf pocket notebook. It could be given at other times, I later discovered, such as failing to get (near) 100% in the termly Latin test. (I never suffered!), for not being quiet in the dormitory, for seniors making a hash in singing in the Cathedral. However, already cowed, I survived my first term without experiencing 'the brush'.

I returned home in December for the Christmas holidays. My parents who were seeing me for the first time in about fifteen weeks must have been curious to note any changes. For one thing I had lost my Wiltshire accent having been teased for saying 'Sirrr' and, because the (very young) assistant master was always commenting on it, my feet were no longer splayed out when I walked. This my parents no doubt observed; but this was also the moment when the dissembling began. It continued for another eight years. So much had been invested in me, so much sacrifice, so much hope for my future. How could I say that I hated the restraints, the fear, the lack of a sympathetic adult to turn to and to give comfort?

Of course, it wasn't all bleak. I made friends and one was never at a loss for something to do: for instance, the stiff card of the weekly service sheets we collected at the end of the week made super gliding darts. They also made hard-hitting missiles for our catapults (made from elastic bands obtained from Bartlett's, the stationers next door to the playground). We also had a number of board games between us, and there were the seasonal 'crazes' - roller skates in the enclosed playground, 'snob', a sort of soft ball cricket, and a form of multiple 'Tag' often played in gangs. During my time there I obtained a microphone that with a battery could be wired to the old wireless in the senior common room. We sometimes used to 'broadcast' from a classroom to the common room, though probably the only ones who enjoyed it were the performers![6]

Note 6. One of the last times I used it was for Roderick's birthday and rigged it from the sitting room to the radio in the dining room. I think the 'announcer' said something along the lines: “We interrupt our programme to wish Roderick Dare a very happy birthday!” I think he was impressed - but then he was only four! (In the distant future, Radio Cornwall!) |

At the start of my third year at the school the 1939-45 war began. I don't remember it having any effect on our lives[7] except for the air raid procedure which we observed on a few occasions when the sirens sounded. Then we went to the basement of the building with our gas masks in their cardboard boxes[8], half below ground level where the kitchens were situated and sat on benches in the corridor.

Note 7. With regard to food rationing, we felt we had always been on it! |

Note 8. We had packets of 52 small playing cards to amuse ourselves till the 'All clear' siren, similar to those found in crackers. |

It was after the war had started that 'Guv' bought a 16 mm cine projector and we then had a new entertainment, usually on a Saturday evening after we had written our letters home. Hinton Lakes, the chemists in High Street, had a library from which we seniors could choose. (I can still conjure up the tinny smell from the shelves of film cans.) They were all silent, but two films I specially remember. One told the tale of a diver in a bulky diving suit with globular headpiece plumbing the depths on Loch Ness to discover the monster. The climax came when the monster looking like a salamander, but much bigger than the man, bit through the air pipe. Finis! The other was called It's a Giff and featured Snub Pollard. His bedroom/living room was filled with Heath Robinson gadgets to make life easy and opened with him in bed. By a series of strings his breakfast was delivered to him on a tray (It included tumbling an egg from the hen's nest near the ceiling down a shute into the saucepan to be boiled). But this was a prelude to the best part when he went into the street, removed the 'b' from the GARBAGE bin, lifted a flap and out slid his little three wheeled 'car'. Removing a huge magnet, he got in, and with it was drawn along behind proper cars. Needless to say the magnet got him into all sorts of scrapes.

After war broke out, there was a craze for buying 'Frog' model aeroplanes with twisted rubber inside the fuselage to operate the propeller. They were designed like the real planes such as the Spitfire and Hurricane. We launched these from the top of the stone steps leading to the song school. We also used to see how high up the steps we could 'launch' ourselves onto the (asphalted?) playground without hurting ourselves, not always successfully!

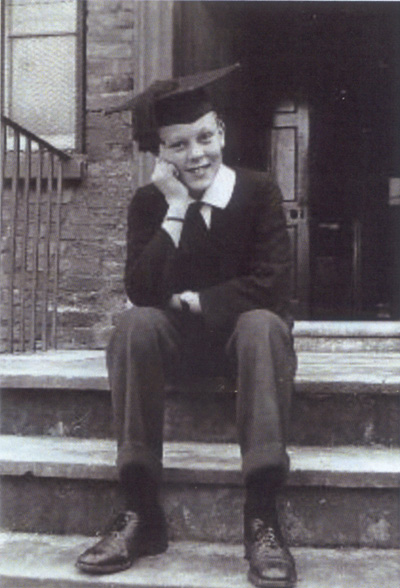

There were four dormitories, named after bishops: Marshall for the seven probationers, nearest to Matron's bedroom; Harrington for the junior boys; Boyd, the largest, for the rest, except for Quivil for the top five boys [Eric is inaccurate here. Marshall and Quivil were bishops (1194-1206 and 1280-1291 respectively), but Archibald Boyd was Dean (1867-1883) and Edward Harington was Canon Chancellor (1856-1881)]. It was in Harrington that I used to read to the others with the aid of a torch from my book of Arthurian legends. Matron caught me and confiscated it - and I was grieved not to have had it returned. In Boyd we got up to all sorts of games in the light evenings of the summer term such as cricket played on a bed with a hairbrush against the pillow for a wicket; a long-handled clothes brush for the bat and a stud (used for our collars) as a ball. On one occasion the brush was used on my bare bottom on the bed by Guv when we were caught. Another mad game was seeing who could drink the water from the wash basins on top of our lockers put out for our morning ablutions (after our cold baths). I remember one boy challenging others to beat him at eating a tube of toothpaste! But especially did I enjoy the singing. I must have been quite promising in this respect since after only one term (which was, I think, unusual) I was to be installed as a full chorister in the choir.

|

Aged 13 with Andrew Rutherford (right) from Uplyme, Dorset, in our daily Services uniform. Eric Dare archive. |

|

In Sunday Eton suit sitting on the steps leading to the front door - not our entrance! Eton collars were worn for all services, weekdays included. As a senior chorister taken in my final year. Eric Dare archive. Keith Gibb archive has an edited version of this photograph and was consequently the origin of this photograph. |

|

Guv dressed for Priest Vicar role. Keith Gibb archive. |

A Full Chorister

St Valentine's Day 1938 was the day I got the 'red hot poker'. The fiction was that as the new chorister waited in the south choir aisle to be fetched by the Head Chorister at Evensong (after the first lesson and before the Magnificat), he would be branded with the Red Hot Poker. I don't think any boy really believed it. The black cassock of the probationers who sat alongside the choir [in the front stall of Cantoris, between the quire stalls and the organ, a practice that still happened into the 1980s, with the stall being called the ‘pros stall’, and by then school uniforms were worn by the probationers. Full choristers were placed in the pros stall during rehearsal and/or service in their cassock as a punishment - ed.] was now replaced by a red cassock and a surplice. I was led into my place at the west end of the Decani choir stall by Head Chorister, Andrew Moseley, who read out the short announcement: 'By virtue of an order from the Dean and Chapter of this Cathedral Church I install you into the place of Alan Baxter'.[9] I still have the Bible cover [now in the Cathedral Library] with the Dean and Chapter's red seal in it, given to every chorister. I dare say the Bible also had the remains of the tiny black lozenges we concealed in its pages for sucking during sermons! I remained on Decani, gradually moved into a more senior position as the years went on.

Note 9. Killed in the war on a motor torpedo boat. Moseley (in c. 2010?) attended the annual ECOCA meeting. |

In my second year I started to sing some solos and I have many happy memories of some of those days in the choir stalls. Highlights include the treble solo throughout the Magnificat in Stanford in G, Mendelssohn's Hear My Prayer as well as the great Wesley anthems. On at least one occasion 'Guv' advised my parents (my father, in fact) to come and hear me as soloist in Wesley's The Wilderness, and doubtless they were pleased. I think I mostly enjoyed the duets and quartets with the lay vicars. One such was Thou Visitest the Earth by Maurice Greene with a long duet for treble and tenor. We had a marvellous tenor, Mr Kennedy, ('Pakenneddy') on Decani and singing with him was a particular joy. My concern that all should go well was commented on some years later by the organist, Alfred Wilcock, ('Baldie') when he came to adjudicate the inter-hall choir competition when I was at Exeter University College. He said he was glad to see me again (some seven or eight years later) and told everyone how, when a chorister, I would turn in my choir stall and conduct the men if they were not singing at the right tempo we boys had rehearsed. (I think the other competitors may have thought that there was some favouritism when Dr Wilcock went on to award the choir cup to my hall, Mardon!)

On Fridays both Matins and Evensong were unaccompanied. Baldie would be at the end of Decani men's stalls with his pitch pipe and from that one note all the music would start while he conducted from the same place. There was none of the present day conducting from the centre aisle that distracts worshippers: on the other days there was no conductor at all - we simply had to listen to the organ and each other. Most difficult were the unaccompanied psalms on Fridays. After the key note was played for the first psalm, subsequent psalms in a different key had to be judged and had to be accurate. On one occasion, before I was one of the six senior boys ('Corners' and 'Middles'), they weren't and the six were given 'the brush' when they returned from the service!

There were a number of regular worshippers for the weekday services; for those sitting behind and opposite us in the honorary canons' stalls, we invented nicknames. A couple who looked somewhat alike we named 1 Timothy and 2 Timothy. When they brought along another man, they were, of course, 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, Titus - we knew our Bible! Another strange looking man used to sit in the canon's stalls after the war had started. From the famous weekly ITMA wartime radio show with Tommy Handley that we listened to when we could, we named him 'Fumph'. But mostly everyone was 'Ma' or 'Pa', though expressed oddly with their surnames. Thus the tenor was 'Packeneddy'. The probationers' teacher, Mrs Treneer, was shortened to 'Ma(y)Tren' and her husband who came on Saturday mornings to teach maths was 'Patren'.[10] He remained so when after Guv's death he took over the school. The most convoluted name was that of Miss Reader (French and Piano) who became 'Marriador'. Another regular was Dean Carpenter's wife who sat in front of him at the entrance to the choir. She always wore so much perfume we could smell her a mile off and, in our childish way, we used to sniff loudly as we passed.

Note 10. Brother of Anne Treneer (author of 'School House in the Wind') |

There were some regular worshippers who supported the choristers. The most generous of all was a Mr Playfair who, besides coming to some services and sitting in the Canons' stalls behind us, would also come to watch us play cricket of a Sunday afternoon after the 3 o'clock Evensong. He would slip us half crowns and pound notes. Since the maximum pocket money the senior choristers were allowed each week was nine pence, this was real bounty - remember that the fees for a whole term were only £5! I don't know how many received his largesse: Andrew Rutherford, our best sports player, possibly; Gordon Exelby, the Cantoris soloist, probably. We had, of course, to hide the money. Since by then I was learning the organ, I hid mine in a pipe in the singing school's organ where I went to practise-provided I could get another boy to pump the bellows.

There were other ways to swell one's pocket money account. We earned half a crown (2s 6d [modern 12.5 pence]) for every wedding and two shillings for a funeral. The general consensus was that funerals were better than weddings since there was not so much to do and they were shorter. The first funeral I was at in the nave had the coffin between the choir stalls. As we sang I was suddenly startled by a noise from the coffin. Not dead? A ghost? No, just the wax falling from a tall candle onto the base!

A valuable memento that I do still have (now in the Cathedral Library) was a book of anthems given for winning the biennial Dean Gamble prize which was competed for by the senior choristers following a term's R.E. I can't remember whether it was on the Acts of the Apostles or the Book of Common Prayer - I was there for both. The usual prize that was asked for was a published book of anthems. It was agreed that I could select my own that came as sheet music. But then they had to be bound - in blue morocco leather, with the Dean and Chapter stamp and tilles embossed in gold leaf. I must have been favoured, for this would have cost very much more than the usual prize. 'Buggy' Belgrove, a fine bass, who copied out the choir's chant books for each member of the choir, kindly and neatly wrote out the index.

Dr Wilcock gave me lessons on the cathedral organ during the last two(?) years. I was allowed to collect the key from the verger's house to get into the cathedral of a (summer's) evening to practise there occasionally. (What trust and security - no alarms!) I deliberately used only soft-sounding stops, but I accidentally touched one of the pistons for pre-set registration under the manuals. Suddenly scores of stops leapt out and a shattering volume filled the building. I practically jumped off the bench. I imagined all the buried dead turning in their graves!

My special interest in the organ began when I was appointed organ 'monitor', responsible for collecting the organist's music after the service and seeing the organist as he was playing the concluding voluntary and turning the music pages. On one occasion, with the sub-organist, John Hinds, playing a particularly fast piece, I turned over two pages - panic! The other duty performed by senior choristers was to serve at 8 o'clock communion on some weekdays.

We had become accustomed to hear the organ playing the Dead March from Saul for funerals; but during the war, the organ was out of action for a while and 'Baldie' accompanied on the grand piano - some said he was a better pianist that organist - but it meant that Chopin's Funeral March, much more evocative than the Handel, was used.

|

Gordon Exelby was the soloist on Cantoris side (I was on Decani) and my 'rival'. Keith Gibb archive. |

Another wartime memory was the way Sunday Matins always ended patriotically, with a national anthem of one of the 'allied' countries. We got to know quite a few, including Norway, Denmark, Holland, Belgium, France, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the USA.

Another incident, probably unique, that caused some consternation began at breakfast one morning when I felt a shiver up my back. It occurred again when we were rehearsing in the singing school. Feeling the corner of my jacket, I discovered a soft bulge and when 'Baldie' was otherwise engaged I produced a pin from my lapel and persuaded the boy next to me to plunge it into the bulge. The jacket came alive and I quickly threw it onto the floor where it continued to move. When we returned from Matins I was told by Nurse that a mouse family had been emptied from the jacket into the bath. We used to buy 'fizzes' which were intended to be put into a tumbler of water to make a fruity drink, but we used to let them fizz on our tongues. Clearly the odd ones in my jacket pocket, hung over my chair in the dormitory had attracted the mice.

I didn't faint then, but there were a couple of occasions it did occur, once at breakfast and another during a service in the cathedral. The doctor said I should keep off chocolate and eggs - not observed very strictly! There was an occasion (not me) when the Cantoris alto, Pa Cotton, carried out a fainting boy slung over his shoulder. When Ordination services sometimes lasted for three hours it's a wonder there were not more fainting choristers.

Every year we were blessed by the Bishop. This took place in the nave stalls at the end of Sunday Matins or Evensong when he would place his hands on each boy's head and mutter a blessing. Before such a service we would make sure that our hair was particularly neat and tidy with lots from the tin of the green 'grease' kept on the vestry table.

Christmas

These days, apart from the weather, we have almost lost the sense of changing seasons. All fruit can be bought at any time and Sundays are no different from Saturdays. And so with Christmas. Now we are subjected to a 'creeping Christmas' that starts almost at the end of summer in the shops, but for us Christmas came upon us with an explosion of colour, light and glorious music. It was indeed "the very best time of the year'.

We wore our funerial black cassocks for Advent (and Lent) and so, when Christmas Eve arrived and we wore our red cassocks with freshly laundered white surplices, and the cathedral was ablaze with light, there was an overwhelming sense of joy. The Decani and Cantoris soloists had the privilege of bringing in Christmas in the ancient 'Grandisson' service after Evensong's first lesson. As Decani soloist for two (or was it three?) years I would softly blow a note from the little metal pitch pipe in my cassock pocket and, holding a candle, appear from behind the high altar, to sing Hodie nobis caelorum Rex de Virgine nasci dignatus est......which was repeated by the Cantoris soloist. We proceeded to the choir and picking up a few more choristers and lay vicars, went through the 'golden gates' and standing in a line on either side in front of the two nave altars beneath the organ, repeated the good news to the nave congregation to be followed by the canticles (King in F?). The service concluded with the choir processing around the nave singing carols at different spots.

|

Andrew Drayton (L) and me with the model of the Eiffel Tower in the 'yard' - our playground. Keith Gibb archive. |

Then it was back to the school for tea and opening our family presents - Christmas morning was going to be too busy to open them then. As we went to bed we put our dormitory bedside chairs out in the corridor with our names on them. Some weeks earlier we had written to 'Father Christmas' (c/o Guv) for a present we would like. When we woke on Christmas Day there they were - and they were not small 'stocking fillers, either. The next (conversion) set for my Meccano was one of mine. In the evening we had a 'slap-up' Christmas dinner together with the Langhorne family and some of his guests, and then out into the 'new' schoolrooms, with the dividing sliding partition opened out for party games. This was just the start, since on most days we were given parties by the clergy. The Dean gave us tea followed by a visit to the Theatre Royal for the pantomime paid for by the Bishop of Exeter. Sitting in the front stalls and very obvious in our Eton suits and collars which we were obliged to wear, we were always picked on by Buttons or Simple Simon to sing the inevitable scene-changing song. Canon Hall gave us tea, then took us to the cinema followed by supper and finally we played 'Murder'. His house in the Close was very old [near the entrance into Southernhay, now the Cathedral Prep school and named after him as Hall House], and was filled with secret passages as well as being haunted - so went the story - but no new chorister was ever let into the secret that, with the lights out, when he ran up the stairs he would be confronted by a 'ghost'. It was Canon Hall with a torch under his surplice. The 'secret passage' was no doubt the back stairs, that the Canon used to be in position before us. The Canon Chancellor McLaren took us to supper at Dellers.

I believe the Archdeacon's treat was the same - in spite of his wife being hit on the nose by a cricket ball lofted over the tall wire fencing that separated the playground from his garden.[10] That given by the Succentor, Reggie Llewellyn, was another cinema visit, I believe. The Bishop of Crediton, whose house [10 The Close, now the Deanery] was next to the school, and on whose lawn we played a sort of bowls in the summer, gave us a party that began with a quiz. The highest mark got first choice of the twenty substantial prizes, one for each according to merit. This was followed by a sumptuous tea and more games. With all the feasting it's a wonder we could sing at all, but the regular round of services continued. On the first Sunday after Christmas the choir went up into the Minstrels' Gallery to sing carols after the main office of Evensong was over. And so it went on until Epiphany on 6th January. The main difference was that we had the run of the school when we weren't rehearsing or singing so that we could play with our new Christmas presents. We also had table tennis, Russian (Bar) billiards as well as the use of the large billiard table.

Note 10. One of his guests who mixed with us one summer was a young Burmese price, 'Poonperm' with beautiful handwriting, as in his autograph. I wonder what happened to him. |

There was also the present Guv gave school each year such as Table Football, or there was his No. 10 Meccano set - the biggest they made - from which we could construct enormous models in one of the schoolrooms. After Evensong on 6th January we packed our trunks to catch the train home for another 'delayed' Christmas.

World War 2

|

In the second major raid on the city 3/4 May 1942 the cathedral was hit as was the school and the HM's house, Abbot's Lodge, that adjoined the school. One of his daughters and two maids were the only ones there and were killed. Easter must have been late that year, and we were still on holiday, after which I went to Blundells Keith Gibb archive. |

|

Abbot's Lodge, one of the oldest buildings in the city. Keith Gibb archive. Eric actually shows a commercially produced postcard of this view in his printed autobiography. |

|

I have difficulty in identifying which part of the building is in ruins, but the wall on the right was part of our playground.Keith Gibb archive. |

|

The choristers, soon after the bombing, were housed in a large building in Honiton where there was a small lake. I visited them from Blundell's after we had broken up. They travelled to Exeter to continue singing on Sundays and, I believe, one day a week. Rowing me is Gordon Exelby. Keith Gibb archive. |

On 3rd September 1939 Hitler invaded Poland. It had been anticipated: men were filling sandbags, sticky tape was crisscrossed over windows to prevent shattering, Dad made wooden frames that had blackout cloth attached; torches had tape across the glass to restrict the light, as did the headlights on cars. We had been issued with gas masks that we had to carry around with us in their brown cardboard boxes. Dad came home with his tin helmet with 'ARP' on it. Since he was the senior warden for our area, his was white - black for the rest. For Roger [long-standing childhood friend at home in Calne] and me, all this activity and change was pretty exciting!

At home on that Sunday we gathered round our wireless set to hear the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, at 11 a.m. make the announcement. The previous year, after Hitler's invasion of Czechoslovakia, he had been given Hitler's assurance that he would not be reclaiming more territory for Germany - he had already taken over Austria and the Sudetenland - and so Chamberlain had returned from Munich and was cheered for his negotiations that allowed him to declare 'Peace in our time'.

I was still on holiday from the Choristers' School, but returned for the new term where the routine was unaltered and the food was just the same. If rationing had started we didn't notice. The only change was the drill for a bombing alert when we all went down to the basement, where the kitchens and maids' quarters were, and sat on benches in the corridor and played cards - the miniature packs that we kept in our gas mask boxes. One boy, Fred Wain, came with a tin helmet given him by his father, a fire officer on the Isle of Wight. I have reason to remember, since we collided round a corner and he, smaller than I, gave me a severe cut on the bridge of my nose that scarred me for years!

In the holidays Roger and I would cycle everywhere: up to Lyneham to see the Wellington Bombers; out to Hilmarton where we helped(?) with the harvest and where in the lunch break I took my turn to ride, bareback, on the trotting cart horse - terrifying! A favourite cycle ride was over the hills past Oliver's Camp to Devizes swimming pool where Roger taught me to swim. One of my birthdays was celebrated when the Stokes family, the Bernards and Dares cycled to Cherhill for a picnic by the White Horse and Monument. The sunny day suddenly had a shower and we sheltered under the distinctive copse above the White Horse.

Although we had a cinema in Calne it didn't receive film reels until they were very old, unlike today's mass distribution. Consequently, we would cycle, often with the Stokes family, to the Gaumont in Chippenham - about six miles away - but up a very long and steep hill - to see the latest movie. If it was a musical we would get the sheet music of the popular songs and Roger and I with Shirley playing the piano would do our imitation of Bing Crosby or Frank Sinatra. (I kept the 40s 'pop' music, melodious with attractive piano accompaniment until we had to downsize; but l remember some of the songs.)

A more extensive ride was with Dad one Sunday on the tandem that he had bought, to Stonehouse, near Stroud to see Aunty Lily and Uncle Frank who had been moved there during the war for his watchmaking skills-precision mechanisms, including giros for aircraft navigation. About 90 miles all round, we reckoned.

I was not aware of any particular privation when I went on to Blundell's; in fact, the national restrictions -clothing, cars/petrol - helped to iron out the class distinctions I was conscious of. When I see old film footage of the hardships of others, especially children, I can't share their suffering or experience. Of course, we were influenced by the war. We learnt to recognize the different aircraft from the booklets produced with the silhouettes of the planes - a bit like birdwatching today! - and we were able to buy flying models of the favourite planes, such as the Hurricane and Spitfire, as well as the Airfix models. At Blundell's I kept a scrapbook after the D-Day invasion of the Allied advance in Europe (still in the 'Archives').

Only in the holidays was I really aware of the changes. Food was rationed and mother experimented with various substitutes - not always successfully - and we had people billeted on us. Initially there were two 14-15 year-old girls from London who were a trial to my parents and who eventually left and were replaced by a Mrs Jeary whose husband joined her when he was on leave. He was in a bomber crew that regularly flew over Europe and eventually failed to return. They were followed by Ken and Marilyn Johns. He was a PE instructor at one of the several RAF camps near Calne: Compton Bassett, Yatesbury and Lyneham. Small as Twyford [name of the family house in Calne] was, as was the spare bedroom, they obviously appreciated the hospitality since my parents kept in touch with them all their lives. As was mother, they were both teachers, Ken becoming a headmaster of a secondary modern school in Croydon after the war. Will Smith ('Smithie') also stayed. He worked for the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC [later to merge with British European Airways (BEA) to become British Airwaysi]). I remember little of him except that he was a reliable forecaster of the weather and was (the only) survivor of an air crash near Paris through sitting in the rear of the plane.

'Holidays at Home' was a feature during the war when the local council put on a fortnight's (homegrown) entertainment in the recreation ground. Reg Stokes, as mayor, was to the fore. I remember going up to the Rec one evening as a spectator when the entertainment(!) was ‘Singing with a Pig’! With a lack of volunteers, Reg Stokes called me up to the stage in the marquee where, having donned an old mac, and accompanied on the piano, I had to sing while holding a wriggling small pig. What embarrassment! The animal should have gone to Harris's first!

One lasting benefit of the wartime period was the experience of having to do without. Life continued and deprivation was manageable. In many cases, the diet we had, even with lack of fruit,11 [Note 11. Mother told me that when Rod [Eric’s brother] was first given a banana (aged 6?), he didn't know what it was.] has stood us in good stead ever since. Apart from the games we still played and the fun that we still could have, there was a corporate spirit where people rallied round. We were used to 'Holidays at Home' and 'Make do and Mend': it probably accounts for my tendency not to spend money on luxuries. - I can't help thinking that growing up in wartime was no bad thing.

Still a Chorister: Another View

It is probably due to the remembered joys of singing in the cathedral that so many old choristers return for the annual get-together on Easter Monday. (Of all the old chorister associations, Exeter is one of the best supported.) But in the case of my generation I often think that it is not unlike reunions of ex-prisoners-of-war - in our case celebrating the fact that we survived the years at Exeter Cathedral Choristers' School. The harshness of the regime, the total want of comfort, the bullying, the poor and limited standard of education, could not be imagined today. I came across this quotation by Canon Edward Norman in The Church Times Jan. 2001: "...it was only in Victoria's reign...that the old and abuse-laden cathedral schools were reformed as a by-product of general reform of endowed schools in the 1870s [and] that regular sung services were revived, and nave services were begun.” I don't think the reformation in the school set-up reached Exeter in my time.

I still remember vividly having to fight David Sayers, who joined at the same time as me, in the schoolroom for some pretended reason; then there was the 'court' the seniors set up to 'try' Roy Bailey, always despised since his surname was the same as one of Guv's. The cause or the result I don't remember, but it was probably trivial. I can remember seeing Cherry being involved, a boy I specially remember since he not only had this exotic name which seemed to suit his fresh, often blushing complexion, (nickname, 'Beetroot') but he also came from some obscure place called Mouse Hole(!) [i.e. Mousehole in Cornwall]

On two occasions boys ran away. I best remember when John Dodd, son of a clergyman and a very good cricketer,[11] together with David Creedy whose home was in North Devon absconded; but they were brought back the following day by 'Guv'.[12] They were two or three years older than me and I wasn't privy to the specific reason, though all the boys knew in advance that they were going to flit. Very likely it was to escape the predations of Langhorne who was a strange mixture. He could be very generous, probably having private means (he had his own family crest - of a 'long horn'). But under this Dickensian regimen, his notion of education was more akin to Whackford Squeers [the cruel headmaster of Dotheboys Hall in Nicholas Nickleby by Charles Dickens.] than to any modern philosophy.

Note 11. His brother was opening bat for Essex and he also featured in county games. |

Note 12. To fund their escape Dodds and Creedy sold some of their things. I don't know how I came to have some money, but in exchange I got Dodds' paintbox, only recently disposed of. Though I never met him after he left, I heard of him as a worker for MRA. It was strange that Creedy should have absconded since his eldest brother was one of the succession of assistant masters we had before they were called up for the services. These young assistants, filling in after their secondary schooling, would have had no teaching qualifications. Certainly, the last one to appear before I left, Keith Gibb, had none. Another of David Creedy's brothers was the first boy we knew to die in the war when the Ark Royal was torpedoed and nearly all the crew were drowned |

To be fair, he taught us classical and correct English so that we could spell words like 'harass' and 'embarrass'; we knew about litotes and onomatopoeia; our punctuation was accurate. Best of all was the issue of ABC of English Usage by Treble and Vallins, a book I still treasure.[13] Another issued to us has also been an invaluable reference book to both Deirdre [Eric’s wife] and me: Carter's Outlines of English History, though the period we 'studied' (I think) was the Stuarts.[14] The most used book with Guv was Allen's Elementary Latin Grammar where the four verbs, Indicative, Subjunctive and Imperative Moods, Active and Passive, together with the five declensions were examined regularly.[15]

Note 13. My current copy is a replacement of the original I had by me for most of my teaching career. |

Note 14. It's strange how odd things stick in the brain, but I recall Guv saying that he had been dandled [i.e. to move up and down held in the arms or on the knee in affectionate play] as a baby on the knee of a man whose (great?) grandfather saw the execution of Charles I. |

Note 15. A 10 shilling note went to those getting 100%, spent at Deller’s [café on the corner of High Street and Bedford Circus, badly damaged by bombing and demolished after the war]; a beating for failure. |

I don't remember any regular timetable of lessons with Guv who taught from his bulging loose-leaf pocket notebook where he kept lists of spellings, marks and 'black marks'. Sufficient to say that we feared his wrath.

Richard William Bailey Langhorne, M.A.

|

Uncaptioned by Eric, but shows Rev. Langhorne by the playground wall. Keith Gibb archive. |

Guv was born on 3rd January, 1879, the elder son of William Bailey Langhorne, of Wincanton, Somerset. He was educated at Sherborne School; University College, Oxford; and Wells Theological College.

Before coming to Exeter he had been an assistant curate in South Petherton, Somerset (1903), at Berkeley ,Gloucestershire, and Chaplain to Sharpness New Dock Co. (1908). In 1909 he was appointed Exeter Cathedral's Deputy Priest-Vicar, and Priest-Vicar the following year.[16] In January 1916, during WW1, he took over as Headmaster of the Choristers' School, a post he held till he died (of cancer) in May, 1944. He married Victoria Winifred H. Poole [known as Winifred], daughter of Hugh R. Poole, of South Petherton, in June, 1906.

Note 16. A Priest Vicar's main role was to sing the responses in choral Matins and Evensong |

He was a commanding figure, over six feet, who during the war generally wore a dark blue corduroy suit. When crepe soles appeared in the shops, Guv bought them but had an additional crepe sole added. Thus, he would fairly noiselessly 'bounce' along! We always knew when he was angry: with us, with the Dean and Chapter (with whom he often disagreed), with Reggie Llewellyn, the Succentor, whose stall on Cantoris was opposite his on Decani; he would thrust a finger between his dog-collar and neck and pulled, literally, 'getting hot under the collar'!

I believe he had a genuine affection for us and showed it by his generosity, giving treats to all the choristers at one time or another and doing his best to secure our further education. He signed himself as 'uncle' in his letters. In fact in his English lessons, among technical terms, already mentioned, he would introduce us to 'portmanteau' words (cf. 'Bakerloo', 'chortle') and encourage us to regard him as 'Nuncle' (as opposed to 'Wuncle' = “wicked uncle').

The senior boys (in Quivil dormitory) used to enjoy the comfort of his capacious, book-lined study after prep and cocoa, lounging on the very sofa we lay prone and bare-bottomed to receive our beatings. We might be given treats as some of us helped him to re-catalogue his library by climbing steps to arrange and call out titles for Guv to enter in his ledger, probably on the advice of insurers when war broke out - only to be destroyed within a year when the school received a direct hit from a German bomb in the Exeter raids in 1942.

‘Baldie' who lived in the Close would sometimes drop in. He would amaze us if we played any note on Guv's piano, high or very low, by identifying it; I don't think we knew people could have perfect pitch. He was fond of his tipple - the Royal Clarence Hotel in the Close was a favourite retreat - and he would join Guv in his nightly routine of whisky drinking.

It was in this semi-drunken state that Guv would come up to the dormitory that housed the five seniors to 'tuck us in' along with Keith Gibb, a former chorister and now the (creepy) assistant master.[17] Sometimes he came with a tin of baked beans and a spoon and feed us.

Note 17. Keith Gibb, who would have been only a few years older than us, in fact, seeing us onto the train at St David's station, would give us Balkan Sobranie cigarettes for the journey. These were very distinctive(and expensive, no doubt) being oval in diameter, not round, and with black rather than white paper and a gold band at the end. |

|

The first page of the letter my father received from Dr Wilcock. Eric Dare archive. |

|

In alb and amice. Worn when serving at the 8 a.m. Communion service, and also for the Grandisson service with the Cantoris soloist when we led with candles. Eric Dare archive. |

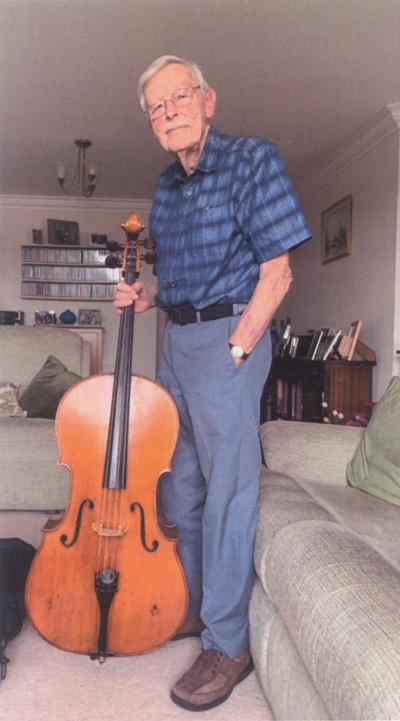

Guv’s appreciation of my contribution to the choir was evident in many ways, including a leaving present of a very expensive watch from Brufords, the premier jewellers in Exeter. More importantly, he was instrumental in getting awards and grants to enable me to go to Blundell's School, Tiverton, as the following correspondence shows:

To RACD [Eric’s father, Reginald Adolphus Cecil Dare] 2 December 1941: (RWBL's underlining [Eric underlined thses pieces of text in his printed version. They are replaced here by italics])

First of all - many, many thanks for your most kind and welcome present [What!?] [Eric’s comment in italics] ...there has been a 'hitch' about Eric's scholarship (now happily disposed of) and the position of the affairs keep changing day to day!

To tell you the whole story would require a volume, and it must suffice to say that, having discovered that Mr Gorton [Blundells' HM] [Eric’s comment in italics] wanted Eric next term and was proposing, as he put it, 'to get the last threads out of his voice', I put my foot down, declining to part with the boy until after Easter term, and stipulating that when he arrived at Blundell's (for the summer term) he should not sing at all. This arrangement has now been agreed to but not without some 'sharp passages' involving many letters and an interview with the Dean and Chapter who finally acceded to my demands.

You have no idea of the difficulties which arise when a body like the Dean and Chapter is confronted with such a question as the case of a boy's voice. You see, there is every prospect that Eric may, later on, develop a fine barytone (sic) voice, but this prospect would be ruined if he were made to sing in the intervening period, and it was my clear duty to see that this did not happen.

All is now well. Eric will, with your approval, return here next term and go on to Blundell's after Easter. I would, most gladly, have kept him here for the summer, but obviously, there had to be 'give and take', and I did not want to risk the loss of his scholarship.

Report for 1st (Spring) term 1941:

Very good work throughout the term. Mathematics especially satisfactory. As a chorister Eric is certainly the best we have had for many years. Dr Wilcock is very well pleased with his progress at the organ, and says that he is likely to become a good performer at this instrument. I am entirely satisfied.

On the back of the termly bill (£9.13.3 plus £1 registration at Blundell's)Spring 1942:

We are more sorry than I can say to part with Eric.

He has achieved an absolutely first rate record in every department of his activities, but, especially, of course, as a chorister in which respect he has surpassed any boy who has ever come within my knowledge or experience. Dr Wilcock said of him this evening that he was a chorister of a quality that one meets 'perhaps once in fifty years'. Not only had he a fine voice, but his qualities as a musician and as a leader were magnificent, and it is quite certainly no exaggeration to say that our very high reputation as a choir is mainly due to him.

Besides this - and even more important - Eric has maintained an excellent character and is beloved by all who have had to do with him.

Without being a 'scholar', he has very good and rapidly developing mental abilities. With all my heart I pray that GOD may bless him.

With kindest regards and deepest gratitude, I am, (RWBL)

I shall be writing to Eric very soon.

From RWBL, Exeter Cathedral Choristers' School at Honiton, Devon, 6 Au(?) 1944

My dear Eric - Heartiest congratulations on this very excellent Report which has given me the greatest pleasure & satisfaction, and thank you very much indeed for the most acceptable birthday present. That was exceedingly kind, as I know that these treats are not easily or frequently come by in these days. (What was it?) [italic comment by Eric]

Best love & every good wish. Let me know when you hear the result of the examination. Ever your affectionate uncle (RWBL)

I wish that tape recordings were in vogue in those days so that I could actually hear what sort of performance I gave. The BBC recorded a couple of carols before one Christmas in which I sang the solo in the Cornelius Three Kings and the treble part in the quartets in Pearsall's In dulci jubilo. I tried to track down the disc from the BBC archives in London when I was attached to BBC Radio Cornwall, but without success. A number of recordings were destroyed in the war. I must have had some ability because a talent scout recommended me for an audition at the HMV studios in Hayes, Middlesex. This had been arranged through Dr Wilcock who told me not to say anything to 'Guv'.[18]

Note 18. As might be inferred from the above, Guv was very protective of his boys and we were not supposed to sing anywhere else, though in the holidays I used to sing at the parish church in Calne and at St Paul's, Chippenham, where my piano teacher, who was responsible for my getting to Exeter in the first place, was organist. |

My parents took me to the studio from the Hayman's in Southall and I was ushered into a large room entirely draped with black velvet curtains in which there was a grand piano and a microphone. Eventually a pianist arrived and asked whether I wanted to do some vocal exercises. We rarely did them at Exeter, so I declined. (How different today!) What I ought to have sung was the opening of Hear my prayer or O for the wings of a dove even though there was no choir to back it - I might have supplanted Ernest Lush! (A contemporary at one of our reunions told Deirdre that he had never heard any soloist sing Mendelssohn's Hear my prayer (i.e. O for the wings of a dove) better than me!). As it was, 'Baldie' suggested I sang I know that my redeemer liveth from Handel's Messiah. Although I had sung it at Exeter I was not so confident; there is little opportunity for the dramatic as in the Mendelssohn, which is what I believe I brought to my singing. Anyway, nothing came of it!